“I don’t know if what you are doing is right or not. I really don’t know. I feel I have to tell you that. But… yes, I will play piano at your wedding.”

That is what I told a friend, in words I can’t recall specifically now, roughly twenty years ago. I had met my friend through the Christian student club at Nipissing University, where I was pursuing an English degree. I’m not sure which year we had that conversation, but in one of our years together my friend, a Pentecostal, was the Bible study teacher for the club and I, a Mennonite, was the club president. (He also played an energetic guitar while singing “I’m Trading My Sorrows.”)

My friend had been married before. I never met his first wife, for she had left him some years previously. He didn’t want their marriage to end, but she made the decision for him. Despite her blatant unfaithfulness, he repeatedly sought to win her back. She refused, and eventually they divorced.

Now my friend had met a new friend, a smiling young lady who also attended the Christian student club and had a ready testimony. After their wedding, they moved overseas where they served as missionaries until she tragically died less than ten years later.

I have a terrible long-term memory, so I can’t tell you any details about their wedding; but I do remember I played piano. The main reason I remember even that basic fact is because of the conversation I had to have with my friend before I agreed to play.

I grew up in a congregation that was first part of the Conservative Mennonite Church of Ontario (CMCO) and then, since my early teens, part of Midwest Fellowship. In that setting I clearly caught, however it was taught, that divorce was terribly wrong and that remarriage was even worse.1 Adultery was certainly no excuse for remarriage, for remarriage itself was adultery. I imagine I learned that through simple presentation of relevant Scripture texts and also through our congregational study of books by people like Daniel Kauffman and John Coblentz.

As I grew older and moved out of our congregational bubble, I naturally met people from other denominations with other understandings of what the Bible teaches about divorce and remarriage. I have never lost my belief that every time divorce happens a marriage has fallen short of God’s design; someone, somewhere, has sinned. And I’ve always remained convinced that there is far too much divorce and remarriage happening among people who claim to follow Jesus.

But I’ve also had persistent, unresolved questions throughout my adult life. What did Jesus mean by “except it be for fornication” (to use the KJV expression)? If divorce is ever justified, when is it? And is remarriage ever blessed by God? What about couples who have wrongly remarried; should they now separate?

A number of years ago I was asked to express my affirmation with a Mennonite denominational position statement on divorce and remarriage. The statement said that initiating divorce or remarrying while a spouse is still living is always wrong and that those who thus remarry must separate. In response, I summarized God’s creation design regarding marriage, divorce, and remarriage. But also, being honest, I added more, including these words:

God’s ideal is crystal clear: marriage should be for life, a mirror of Christ’s loving relationship with the Church. God’s perspective on less-than-ideal situations is not always so clear. I notice that the NT texts about marriage (both Jesus’ words and Paul’s teachings) are presented as discussions of what a Christian should do. They are not directly presented to answer every question of the appropriate response of either a repentant Christian or the church after this ideal has been violated. Thus we rely on exegetical and theological deduction when we address questions like, “What about someone who has already divorced and remarried and now wants to faithfully honor Christ?” While such secondary questions are crucially important, I think it is honest and helpful to observe that no NT text appears to have been directly intended to answer that question. Most attempts to answer such questions either rely on the witness of church history or are based on important but slender and difficult exegetical data.

I am confident that my experience is not unusual among those of us who have grown up in the conservative Anabaptist world.2 Many of you, I’m sure, could tell similar stories. Others of you, who are more confident in your interpretations on this topic, could probably tell stories of when your beliefs bumped up against differing beliefs within our own conservative Anabaptist world.

The diversity and uncertainty of conservative Anabaptist beliefs about divorce and remarriage were driven home to me recently in an informal poll I conducted on Facebook.

I was curious how accurate my hunches were about how conservative Anabaptists handle Jesus’ exception clauses. Here, to refresh our memories, are the two times Jesus mentioned some exception to his prohibition of divorce:

But I say to you that everyone who divorces his wife, except on the ground of sexual immorality, makes her commit adultery, and whoever marries a divorced woman commits adultery. (Matt. 5:32)

And I say to you: whoever divorces his wife, except for sexual immorality, and marries another, commits adultery. (Matt. 19:9)

The two clauses are very similar and are usually understood to mean the same thing. But how do conservative Anabaptists handle them? I created a poll to find out.

I’ll share the results of that poll here and use it as a springboard for discussion. You are also welcome to add your own responses in the comments below.

Here is the poll I presented:

In your experience, what are the most common ways that conservative Anabaptists handle Jesus’ exception clauses in the Matthew 5 and 19 passages about divorce and remarriage? Which of the following is most common in your experience?

A. The exception refers to fornication during the Jewish betrothal period. It allowed for “divorce” from a betrothed “wife” or “husband” and gave permission to marry another. It has no application for married couples today.

B. The exception refers to adultery after marriage. It allows for divorce (or separation) only, but no remarriage.

C. Either of the above are equally possible as a matter of biblical interpretation; what is clear is that Jesus is prohibiting remarriage in all cases.

D. Focusing on exception clauses is just looking for loopholes; let’s focus on Jesus’ and Paul’s clear teaching instead.

E. Some other approach?

I’m not asking what you believe, just trying to see if I’m discerning the most common approaches within the conservative Anabaptist world. Thanks in advance for your help!

A brief explanation is in order about options A and B above.

Option A is what I will call the “betrothal” view. This view says that Jesus’ exception clauses refer only to the Jewish practice of betrothal, not to fully married persons. A Jewish person who entered a betrothal covenant was already called a husband or wife, even though the wedding might not happen for another year. They could have their marriage annulled (the term “divorce” was even used) if unfaithfulness was discovered in their partner. They were then completely free to marry another. This is what Joseph initially planned to do with Mary when he discovered she was pregnant (Matt. 1:18-19).

Option B is what I will call the “divorce-only” view. This view says that Jesus’ exception clauses refer to fully married persons. According to this view, Jesus is giving permission for a married person to divorce their spouse if that spouse commits sexual immorality (usually defined as adultery). Jesus was not, however, giving permission to remarry.

Now to the results of the poll. Sixty-four people answered this poll, representing a fairly diverse range of conservative Anabaptist church influences in at least twenty American states, two Canadian provinces, and Mexico. It is not possible to tally the results with scientific accuracy, for some people gave multiple or qualified responses. But the general picture is clear enough.

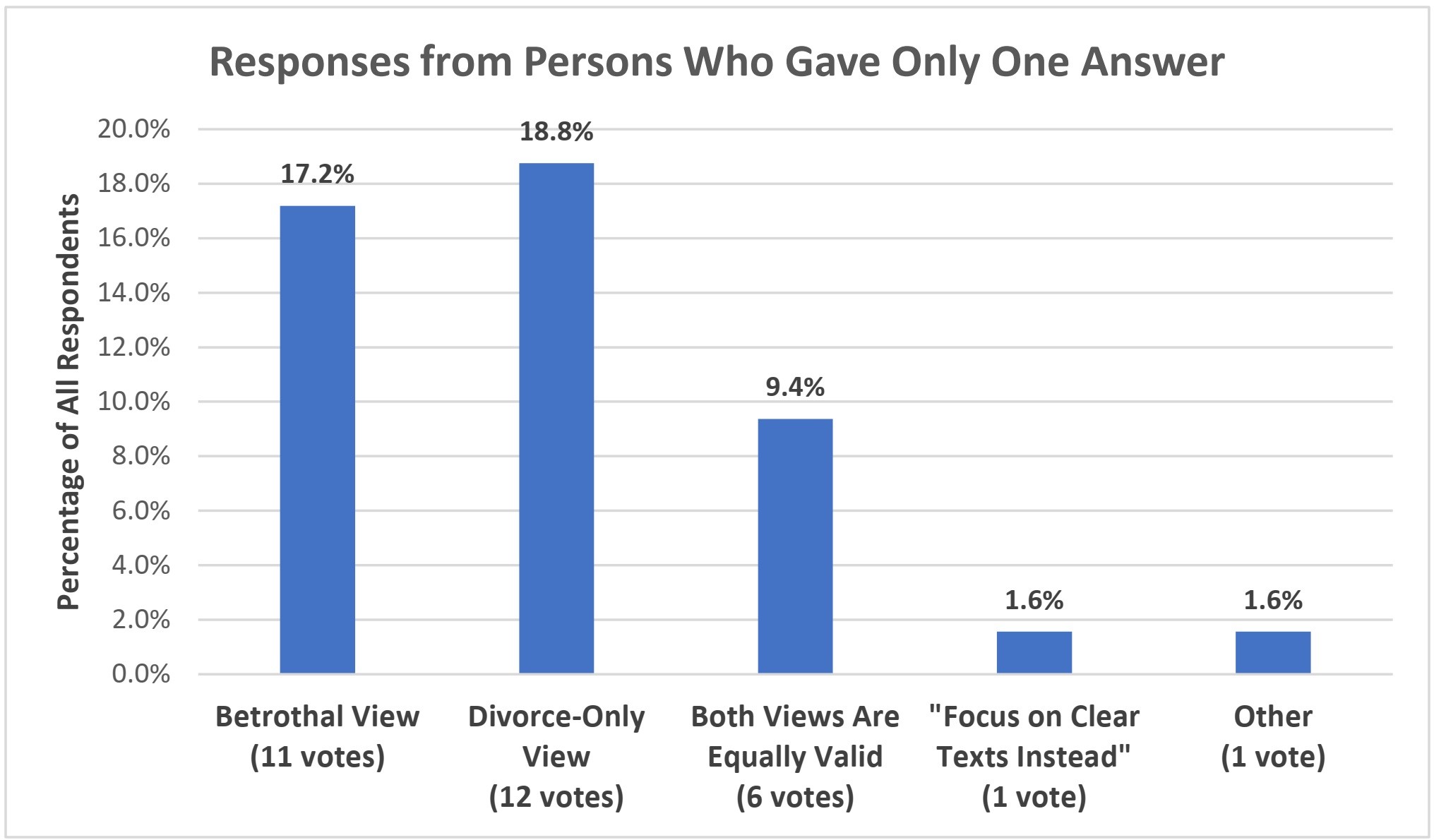

First, here are the responses from respondents who offered only one answer to my poll, shown as a percentage of all respondents. (The raw vote total is included below each heading.) For example, about 17.2% of all 64 respondents (11 people) said they have heard only the betrothal view taught:

(You can enlarge the images by clicking on them.)

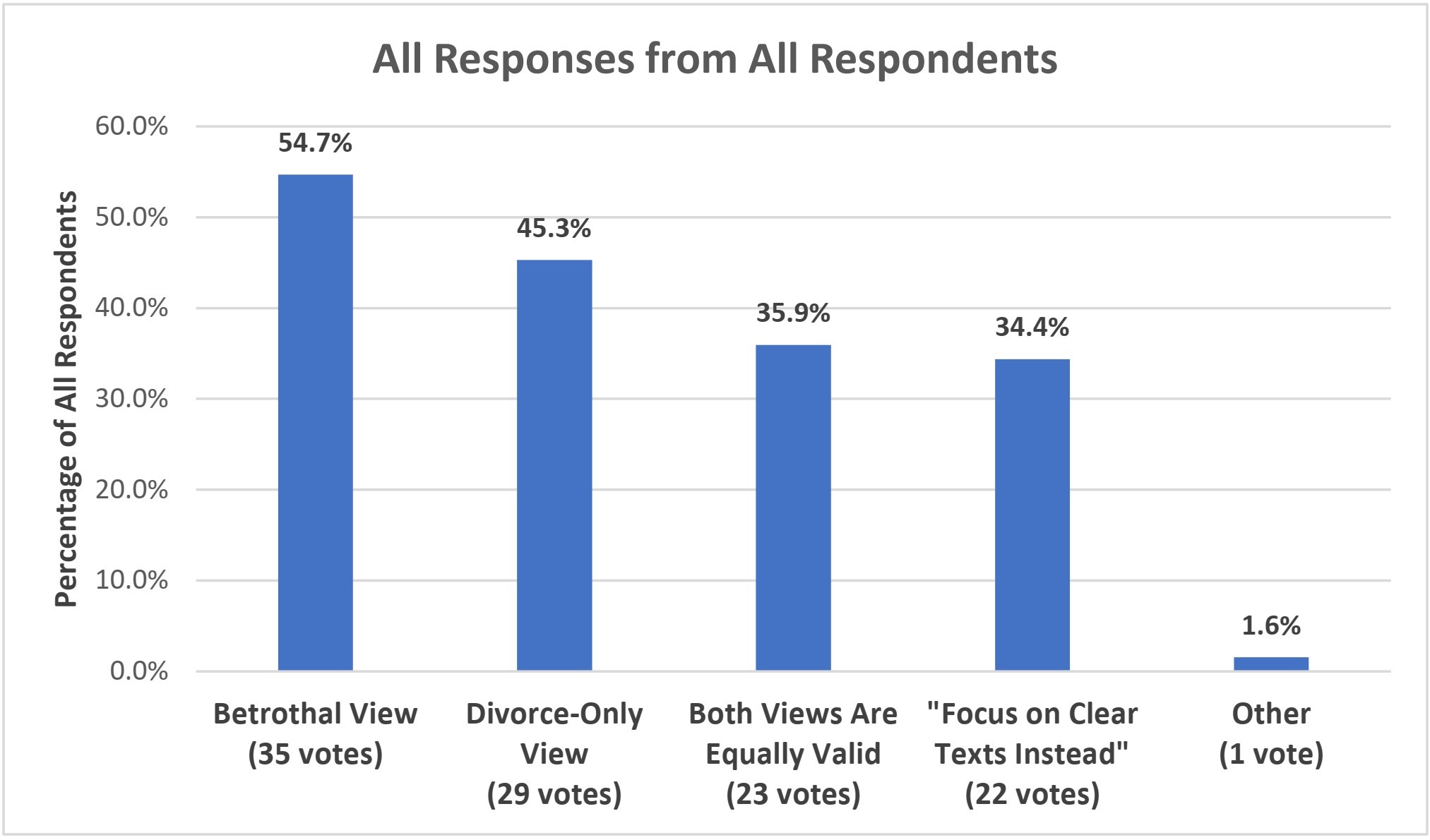

Here is a record of all responses, showing how many times each answer was mentioned in any way. Many people gave answers like “Mostly A, but also sometimes D.” In such a case, this chard treats both A and D alike, without recognizing that A was prioritized over D. For example, about 54.7% of all 64 respondents (35 people) said they have heard the betrothal view taught, whether often or rarely:

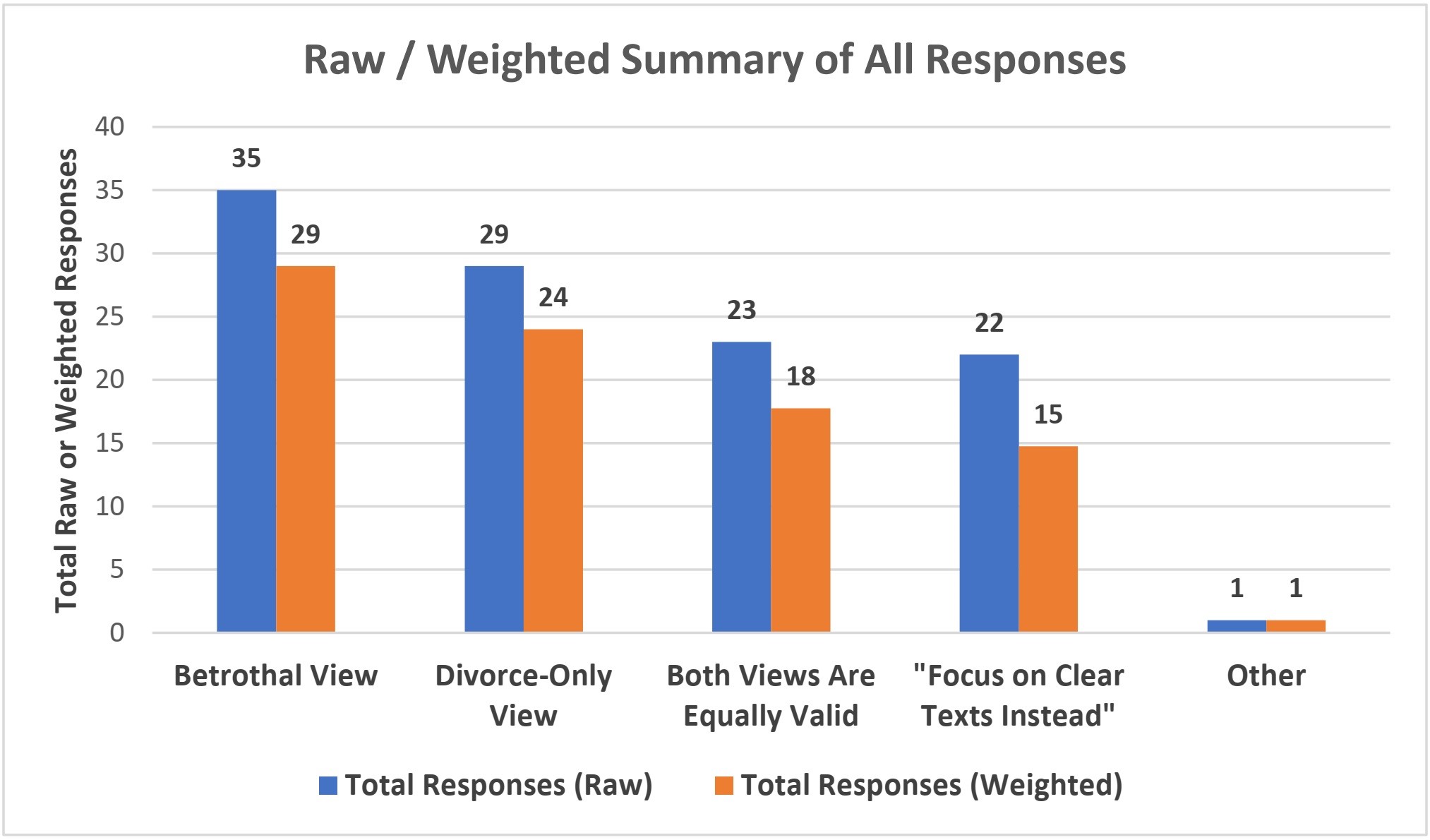

Finally, here is another graph displaying all responses, also including (in orange) a rough attempt to represent the weight respondents intended for each answer when they gave more than one answer:

How can we summarize these results?

- My hunches were probably right; only one person suggested an alternative conservative Anabaptist approach to Jesus’ exception clauses, which was really option D with some ugliness added.3

- The most common approach is probably the betrothal view, mentioned by over half the respondents. My perception is that many Anabaptists today have encountered this view through popular-level Protestant teachers such as Bill Gothard and Joseph Webb (Till Death Do Us Part? What the Bible Really Says About Marriage and Divorce). More professionally-published sources have also been influential, such a paper by John Piper (“Divorce and Remarriage: A Position Paper”) and a recent multi-authored book called Divorce and Remarriage: A Permanence View. I am not sure when this view entered Anabaptist circles, but already in 1950 John L. Stauffer was promoting it,4 and in about 1992 John Coblentz wrote that “this view has had wide acceptance among conservative people.”5 Note: This paragraph originally indicated that J. Carl Laney promotes this view, but I was mistaken.

- The divorce-only view is also very popular among conservative Anabaptists, mentioned by nearly half of the respondents. This view appears to have somewhat longer roots within Anabaptism (more on that in another post), but Protestant scholars such as Gordon Wenham and William Heth (Jesus and Divorce) have also been influential within some Anabaptist groups. Anabaptist influencers David Bercot (“What the Early Christians Believed About Divorce and Remarriage”) and Finny Kuruvilla (“Divorce and Remarriage: What About the Exception Clause?”) are also promoting this view through their summaries of early church practices.

- Over a third of respondents have heard both the betrothal and divorce-only views presented as being equally-valid interpretative options.

- Over a third of respondents have heard warnings against looking for loopholes and encouragement to focus on clearer texts instead of the exception clauses.

What can we learn from this poll about how conservative Anabaptists approach Jesus’ exception clauses?

For most of the rest of this post I plan to discuss some weaknesses I perceive in some conservative Anabaptist approaches to these words of Jesus. I will cite specific examples to support my observations. Please know that when I name names, I have absolutely no desire to belittle anyone. People whom I highly respect and love as past mentors and teachers are among those who may feel challenged by some of my words. This is a difficult topic and many good Christians have not reached full agreement. Part of me does not want to name names, but I think citing some public documents can make this discussion more fruitful. My desire is simply that together we will learn to better hear and understand Jesus’ words. If you feel I am mishandling his words, you are welcome to let me know.

With those expressions of love in mind, here are four general observations about the poll results:

First, it appears that most conservative Anabaptists do not rely on or allow these exception clauses to determine their theology and ethics of divorce and remarriage. Rather, for these texts, their desired theological ends justify their uncertain interpretive means. Why are only these two specific interpretations (betrothal and divorce-only) currently popular among conservative Anabaptists—especially since these interpretations are very much the minority within Protestantism, Roman Catholicism, and the Orthodox Church? It is surely because, rightly or wrongly, many conservative Anabaptists have their minds made up about what Jesus could not mean before even considering these texts.

An example of this is a tract available from the conservative publisher Rod and Staff. It rebukes those who use Jesus’ exception clause as a loophole but never offers a positive interpretation of what Jesus actually did mean:

Sometimes the exception clause in Matthew 5:32 is used to support divorce in cases of unfaithfulness. But such reasoning cannot be reconciled with the other New Testament passages on divorce and remarriage, which are very clear in their statement. The hardness of heart would grasp for a loophole here and fail to reckon faithfully with the clear statement of God’s Word in a number of other passages. This is hardly a safe approach to the Word.6

Second, it is clear that conservative Anabaptists have not reached a consensus about what Jesus did mean when he said “except it be for fornication.” They do not even agree on whether this clause has any direct relevance for Christians today or whether it was something spoken only for Jewish listeners.

Here I want to emphasize an important side point: If the betrothal view is correct, then we have zero verbal permission from Jesus not only for remarriage, but also for separating a marriage for any reason whatsoever. According to this view, Jesus’ words “Let not man separate” are given no qualification whatsoever for married couples—only for those who were betrothed. If we are going to allow for any separation of married persons (even when we don’t call it divorce), we have to assume that Jesus would have been okay with it and find possible justification elsewhere, such as from Paul in 1 Corinthians 7:11. This assumption may indeed be valid; maybe we should consider the possibility that Jesus sometimes used typical Jewish hyperbole in his teaching. But if we adopt this interpretation, we must be honest: we are affirming that an unspoken qualification is attached to Jesus’ words, “Let not man separate.” We are saying, “Jesus said ‘Let not man separate,’ but we know that there are times when he would approve of separation anyway.”

Third, many conservative Anabaptists are deeply uncomfortable with these exception clauses. Truth be told, they would be happier if Jesus had not spoken them. These clauses throw a wrench into the otherwise clear teaching of Scripture. The term “exception clause” makes it feel too much like Jesus is “making an exception” for something that is intrinsically evil. If you’ll pardon another pun, many conservative Anabaptists “take exception” to Jesus’ exception clauses. This is evident in several of the examples I share in this post.

Fourth, when conservative Anabaptists do try to explain Jesus’ exception clauses, they are often quite happy to present mutually opposing interpretations as equally possible. As long it can be shown that there are ways these exception clauses can possibly be harmonized with other biblical texts that appear to forbid divorce and remarriage, many conservative Anabaptists are content not to decide between contradictory interpretations.

I want to underscore that the two popular conservative Anabaptist interpretations of Jesus’ exception clauses indeed sharply disagree with each other on an exegetical level.

In pastoral practice, the two probably lead to similar results in conservative Anabaptist churches. The divorce-only view allows a believer to divorce from an adulterous spouse; but is rarely put into practice. The betrothal view technically does not give authorization for any sort of separation; but, as with the divorce-only view, sometimes separation is permitted for a variety of difficult circumstances without any direct authorization from these texts. Most importantly, both approaches strongly prohibit any remarriage, so the practical results are similar.

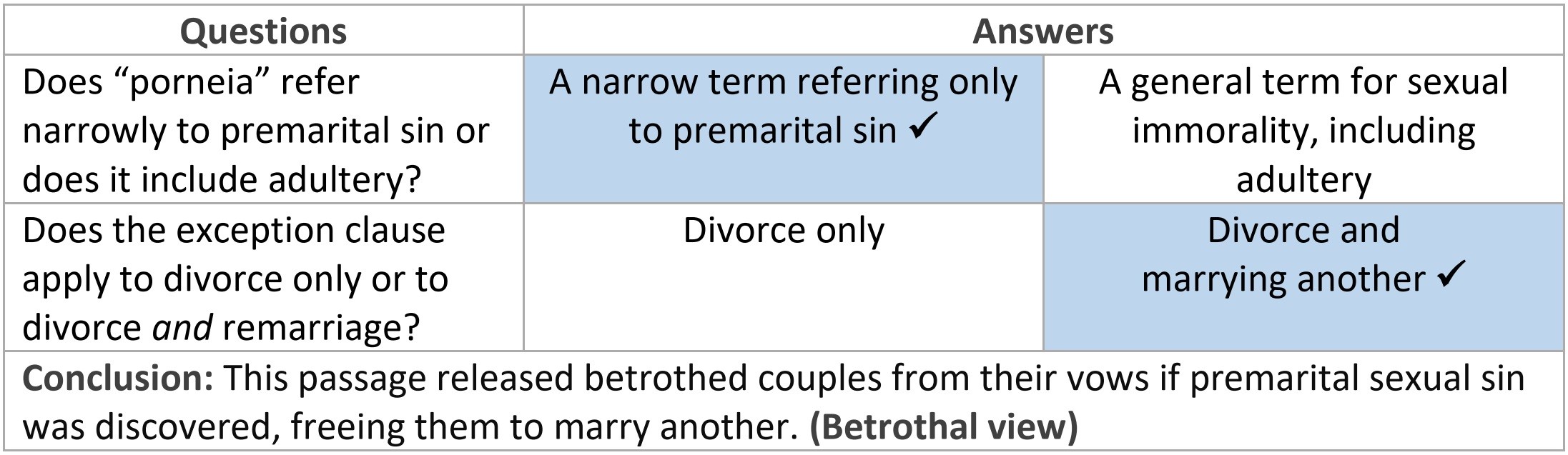

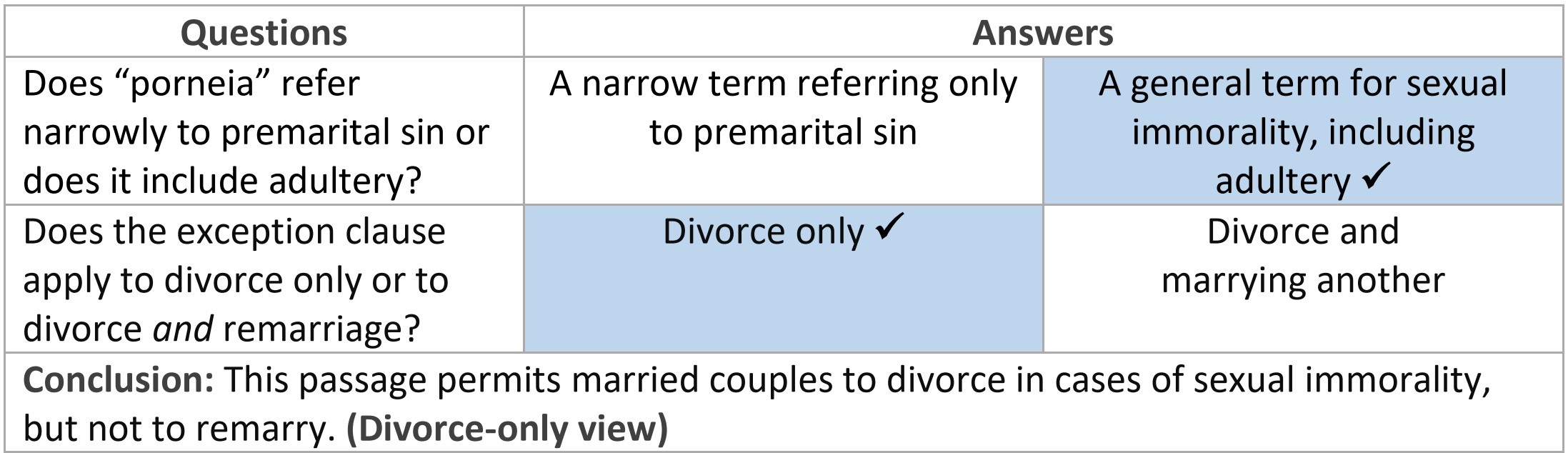

Despite the similar theological and practical results, on an exegetical level these two views are diametrically opposed. There are two key exegetical questions that must be solved to properly understand Jesus’ exception clauses:7

- What do the exception clauses themselves mean? Especially, what does porneia (πορνεία; the word translated “fornication” in the KJV) mean? This is a lexical question, a problem of word definitions.

- How do the exception clauses fit within Jesus’ complete sentences? In particular, in the Matthew 19:9 exception clause (which is where much of the debate is focused), does the exception clause modify only what comes before it, or does it modify Jesus’ entire statement? That is, does it identify an exception for divorce only, or also for marrying another? This is question of syntax, or sentence structure.

On these two key questions the betrothal and divorce-only views completely disagree. On the first question, the betrothal view says that porneia refers narrowly to premarital sin—fornication. But the divorce-only view says porneia is a more general word referring to a variety of sexual sins, including adultery.8

On the second question, the betrothal view says the exception clause modifies the entire subject-portion of Jesus’ sentence (“whoever divorces his wife and marries another”). Thus, Jesus was recognizing an exception for both divorce and marrying. What Jesus was really saying in Matthew 19:9 could be paraphrased like this: “Whoever divorces his wife and marries another commits adultery, except if his betrothed wife commits sexual immorality; then he is free to divorce her and marry someone else.”

The divorce-only view, in contrast, says the exception clause modifies only the first half of the subject of Jesus’ sentence (“whoever divorces his wife”). Thus, Jesus was recognizing an exception for divorce only. Jesus’ statement could be paraphrased like this: “Whoever divorces his wife and marries another commits adultery, except if his wife commits sexual immorality; then he may divorce her, but remarriage would still be adultery.”

The exegetical disagreement between these two views can be summarized in chart form.

Here is the exegesis that leads to the betrothal view:

And here is the exegesis that leads to the divorce-only view:

Given these distinct differences, a thoughtful reader needs to come to a confident conclusion on only one of these two questions to eliminate one of these views (betrothal or divorce-only) as a possible reading.

The betrothal interpretation of the second question (about syntax) demands further comment. I get the sense that few people take time to consider the implications of how the betrothal view interacts with the syntax of Jesus’ statement; most discussions of this view focus on the lexical question instead, along with possible supporting historical evidence.

The betrothal view, however, demands that we understand Jesus’ exception clause as modifying both the divorce and marriage parts of the subject of his sentence. If this were not so, then Jesus would have been saying this: A betrothed person who discovers that their husband or wife has been sexually unfaithful may be released from the betrothal covenant, but they may never marry anyone else. This proposal is self-evidently and historically unreasonable.

(It may be useful to point out that Jesus does not say “remarry” but “marry another.” Further, as I understand it, the Greek can be understood to say “marry an other”—referring not to a second woman but a different woman.)

The point I want to emphasize here is that, if the exception clause does not modify the marriage part of Jesus’ statement, the betrothal view is impossible.

This fact is sometimes missed. In a Christian Light Publications book, for example, Coblentz notes how the exception clause comes after Jesus’ mention of divorce and before his mention of adultery. Based on this sentence order, he concludes that “the exception refers to the putting away.”9 Despite establishing this firm conclusion, Coblentz later says, “Unfortunately, seeing the exception clause as referring to the ‘putting away’ does not resolve all the controversy.”10 After this statement, he proceeds to discuss the strengths of the betrothal view. In the end, he seems to prefer the divorce-only view, but he still affirms the betrothal view as possible.11

Clair Martin, in an official publication of the Biblical Mennonite Alliance, relies significantly on Coblentz. He agrees that the betrothal and divorce-only views are “both in line with scripture.”12 He examines only the lexical question of the definition of porneia and never addresses the syntactical question of how the exception clause modifies Jesus’ statement. He seems unaware that this factor also separates the betrothal and divorce-only views. His main concern seems to be to close “one of the most prominent loopholes that people use to get around this subject.”13

The inverse, of course, is also true: If you are going to say that the betrothal view is a valid interpretive option, then you must acknowledge that one of the most commonly-cited arguments in favor of the divorce-only view is not conclusive: The syntax of the sentence does not prove that Jesus is making an exception only for divorce. This means, if we are honest about our exegesis, that those who promote the betrothal view should acknowledge that the syntax of the sentence also permits Jesus to be making an exception for both divorce and (re)marriage.

What does it say about conservative Anabaptists that so many are content to hold mutually-contradictory interpretations as equally valid? Positively, it reflects a determination to honor the teaching of Scripture that is understood to be clear, without letting disputed texts prevent obedience. It could also reflect exegetical humility—an awareness that the Bible is not always as plain as our Anabaptist heritage likes to claim.

Negatively, it could reflect the fact that most conservative Anabaptist church leaders have never studied Jesus’ exception clauses carefully; indeed, that they are not equipped to do so. It could also reflect a proof-text approach to Bible interpretation and systematic theology that does not sufficiently consider the original literary and cultural contexts of the biblical texts. More positive and negative implications are surely involved, and not everyone who takes a both-and stance shares the same mix of positive or negative motivations.

One way to avoid such tension, of course, is to simply ignore Jesus’ exception clauses altogether (response D in the poll). Two particularly clear examples of this are provided by publications from the Southeastern Mennonite Conference and the Beachy Amish-Mennonites.

The former group adopted a “Statement of Position on Divorce and Remarriage” in 1983. This statement lists both Matthew 5:32 and 19:9 among its proof texts, but never quotes them and never makes any mention of “fornication.” It does quote (with commentary) Mark 10:11, which is parallel to Matthew 19:9 except for the crucial difference that it lacks the exception clause: “Whosoever shall put away his wife, and marry another, committeth [or continues to commit] adultery against her.” Avoiding Jesus’ exception clauses altogether, this statement simply states, “The act of adultery does not dissolve the marriage bond.”14

A doctrinal position statement ratified by Amish Mennonite (Beachy) ministers in 2003 takes a similar approach. (In fact, though it presents itself as an original publication, it is obviously an adaptation of the former document, virtually identical in many sentences and following the same overall structure.) This statement cites seventeen different passages of Scripture, including some verses from Matthew 19. But it never once cites or alludes to either of Jesus’ exception clause statements (Matt. 5:32; 19:9). Romans 7:1-3 (or a particular interpretation of that text) is cited in whole or part seven times in this brief document and clearly serves as the interpretive lens through which all other texts are read—or excluded.15

The approach exemplified by these two documents, while understandable on one level given the desire to uphold God’s creation design for marriage, is functionally dishonest in its handling of Jesus’ words. We do not honor Jesus when we avoid his “hard sayings” and quote Scripture selectively to support our theological positions. We do not serve God’s people well, either, when we do this. Unfortunately, this approach is a relatively common way that some conservative Anabaptists “solve” the topic of divorce and remarriage.

What is a better way to solve the interpretive dilemma of Jesus’ exception clauses?

Are there better options than either (a) promoting two mutually-contradictory interpretations of Jesus’ words or (b) pretending he never said what he did? What solution might conservative Anabaptists be likely to adopt?

Without professing prophetic ability, I suggest several possible outcomes. First, either the betrothal or the divorce-only view may be successfully championed by someone until it becomes the consensus view. This would significantly shore up the goal of preserving a rare-divorce, no-remarriage culture in conservative Anabaptist churches. And I must emphasize that nothing I have written in this post proves that either of these two views is wrong, even though I do see some weakness in both that are beyond the scope of this post.

Second, if a significant consensus is not reached, I suspect a growing number of people, observing the uncertainty, will question the current conservative Anabaptist approach to divorce and remarriage more broadly. We will continue to see people, either quietly or publicly, walk away from the unqualified no-divorce, no-remarriage teaching they have absorbed.

It must be acknowledged, after all, that there are not only two possible ways to deal with Jesus’ exception clauses. There are several views that are similar to the betrothal view, for example, which suggest that Jesus was referring to incestuous or otherwise unlawful marriages. Others have proposed, without any hard evidence, that Matthew added the exception clauses in an attempt to tone down Jesus’ rigid stance against divorce and remarriage (which is different from the proposal that Matthew added the clauses to accurately reflect Jesus’ unspoken assumptions). Still others argue that the exception clauses are not really exceptions at all, but rather Jesus’ way of saying that he was making no comment on the Deuteronomy 24 exception that the Pharisees asked him about (the “preteritive” view).

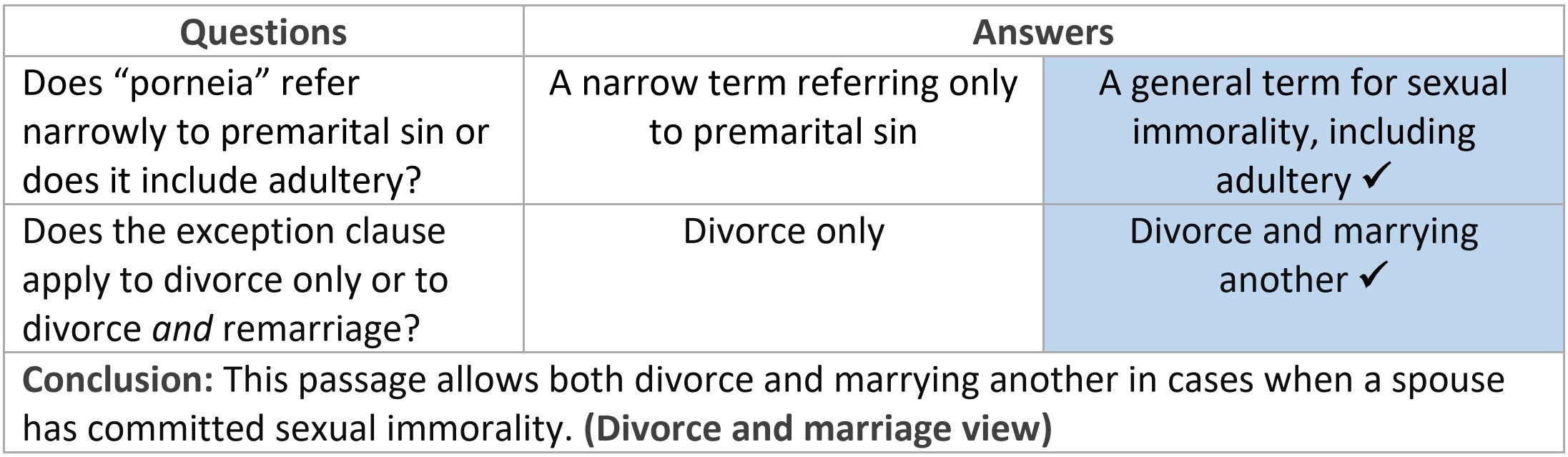

But apart from either adapting the betrothal view or finding a way to functionally remove any exception from Jesus’ lips, there is also the possibility of revisiting how our two key exegetical questions might fit together.

There are two primary options. One option makes little sense, as we noted above; there is no good reason to imagine Jesus was prohibiting betrothed persons from ever marrying if their first betrothal was ended by the discovery of sexual immorality:

The other option is that Jesus was recognizing that both divorce and marrying another are honorable options when a spouse (or betrothed person16) violates a marriage through sexual immorality:

For conservative Anabaptists, the problem with this last view is not only that it appears to directly contradict clear Scriptures that prohibit both divorce and remarriage; it also is the most common Protestant way of interpreting Matthew 19:9.17 This, to many conservative Anabaptists, makes it doubly suspect and likely to undermine their Anabaptist vision of obedience to Jesus.18

How, then, are we to resolve this dilemma that conservative Anabaptists have with Jesus’ exception clauses? One necessary solution, most certainly, is to engage Scripture more closely in search of more sure answers. In doing this crucial task, however, I suggest that we also take a closer look at our own Anabaptist heritage.

You may be surprised, as I was, to learn that it is only in recent history that Anabaptists have taken exception to Jesus’ exception clauses. But that is a story for another post.

Thank you for reading. Please pray for me as I continue to study and write, and please share your insights in the comments below!

If you want to support more writing like this, please leave a gift:

- The congregational “Statement of Faith and Practice,” as of 2002, simply says, “Divorce and remarriage is contrary to God’s Word.” Constitution and Statement of Faith and Practice of the Otter Lake Mennonite Church, Revised Constitution 2002, pg. 14. ↩

- I normally use that term as it is commonly used in my world, to refer to anyone from Amish or Mennonite churches that range from Old Order churches on one “end” to roughly the Biblical Mennonite Alliance on the other “end.” In this post I am referring mostly to the car-driving subset of that group, since I have almost no direct experience with Old Order groups. ↩

- He described like this: “I grew up in Joe Wenger Mennonite church. My takeaway would be that they are teaching no divorce for any reason. Yet, if you leave or show any inclination to leave, they’ll gladly try to take your spouse aside and try to convince them you’re off in the head. My point being, in teaching not acceptable but in action there are plenty of divided marriages. The go-to verse would be, ‘In the beginning it was not so, but through the hardness of your hearts,’ etc.” ↩

- John L. Stauffer, “Biblical Principles–Divorce and Remarriage,” The Christian Ministry, Scottdale, PA, III, 3 (July-September, 1950), 89-94; as mentioned in an annotated bibliography by J. C. Wenger, Separated Unto God (Harrisonburg, VA: Sword and Trumpet, 1990; orig. pub. Scottdale, PA: Mennonite Publishing House, 1950), 182. ↩

- John Coblentz, What the Bible Says About Marriage, Divorce, and Remarriage (Harrisonburg, VA: Christian Light Publications, 1992), 34. This booklet is available in full online: https://anabaptists.org/books/mdr/ ↩

- “Divorce—Is It Lawful?” 12-page tract (n.a., n.d.), Rod and Staff, 5-6. Accessed online, June 20, 2020. https://www.milestonebooks.com/item/1-3104/ ↩

- Gordon Wenham says that interpretations of Jesus’ Matthew 19:9 statement “hinge on two main issues”: “the meaning of the Greek term porneia” and “the grammar of the exception clause” in relation to the rest of the sentence (Gordon Wenham, Jesus, Divorce, and Remarriage: In Their Historical Setting (Bellingham, WA: Lexham Press, 2019), 78). Both the nature of Jesus’ statement and my reading of other authors confirm Wenham’s claim. ↩

- Some suggest it refers narrowly to adultery, but that position is harder to defend on lexical grounds and also unhelpfully excludes other forms of sexual immorality that married persons may commit, such as homosexual relations or bestiality. ↩

- Coblentz, ibid., 29. ↩

- Coblentz, ibid., 34. ↩

- Coblentz, ibid., 38. ↩

- Clair Martin, Marriage, Divorce, and Remarriage: A Biblical Perspective, Biblical Perspectives on Present Day Issues, #2 (Publication Board of Biblical Mennonite Alliance, 2010), 6. ↩

- Ibid., 6. ↩

- “Statement on Divorce and Remarriage,” (Southeastern Mennonite Conference, 1983). Available online, as copied by a student of Mark Roth: https://www.anabaptists.org/tracts/divorce2.html ↩

- “Marriage, Divorce and Remarriage” (Sugarcreek, OH: Calvary Publications: 2003). Available online: http://www.beachyam.org/librarybooks/beliefs/marriage.pdf. A note at the beginning of this statement says this: “This doctrinal position statement was formulated by a five-man bishop committee and ratified by the Amish Mennonite (Beachy) ministers…” I presume the five bishops were Beachy, not Southeastern Mennonites. ↩

- In this approach, Jesus’ exception clause explains Joseph’s plan to divorce Mary while also referring to sexual betrayal within marriage; sexual unfaithfulness is seen to permit divorce and marrying another at any stage of the relationship. ↩

- It must be noted, however, that merely adopting this reading of Matthew 19:9 does not mean one agrees with most Protestants on the topic of divorce and remarriage in general. Most Protestants allow divorce and remarriage not only in cases of adultery, but also in cases of desertion, citing a “Pauline privilege” in 1 Corinthians 7:15. In addition, many Protestants say that “other actions that break the marriage covenant such as physical abuse” are also grounds for divorce and remarriage (Andrew David Naselli, “What the New Testament Teaches About Divorce and Remarriage,” Detroit Baptist Seminary Journal 24 (2019): 3–44, pg. 5. Available online: http://andynaselli.com/wp-content/uploads/2019_Divorce_and_Remarriage.pdf). ↩

- I have learned that this wariness about Protestants surprises some of my friends who are not from Anabaptist roots. For such readers, here are a few excerpts from a twenty-page Rod and Staff Publishers tract titled “More than Protestantism: The Thrilling Story of a Church Founded upon Christ”: “Born-again Christians everywhere are being urged today to work toward the revival and unification of Protestantism. Before we rush to make common cause with this ecumenical movement, let us look at the record of history… At first Luther and Zwingli defended the principle of liberty of conscience and denounced all persecution, but, tragically, both leaders depended heavily upon the support of favorably inclined secular rulers… This eventually involved them in the use of persecution against religious dissenters… Many born-again Christians at this point began to break with Protestantism… A long and bloody persecution ensued in the next 50 years, in which from 20,000 to 50,000 of these New Testament Christians were martyred by the Roman Catholics and the Protestants… Thus these churches founded upon Jesus Christ and His Word had to break with the compromises and evils of Protestantism, just as the reformers ultimately broke with the Catholic organization… They were called ‘Anabaptists’ (rebaptizers) by their enemies because they practiced believer’s baptism… But the main difference between the Anabaptists and their opponents was not the question of baptism, but the question of the relation between the church and the rest of society… It is a sad fact of history that all the prominent reformers approved of persecution and death for the Anabaptists. A certain Baptist scholar of our own time discovered through exhaustive research that more Anabaptists were put to death for their religion by the Protestants than were similarly put to death by the Roman Catholics!… ‘Why not Protestants?’ you may be asked. The record of history shows us the answer clearly: from the false teachings of Protestantism… come the hellish evils of the unholy alliance between State and Church, the persecution of religious dissenters, the ‘religious’ wars that killed millions, modern nationalism, racism, and dictatorship! Surely Protestantism is only another ‘lamb-like beast’ drunken with the blood of the martyrs!” ↩