This is the second of several historical posts surveying how Anabaptists have interpreted Jesus’ exception clauses (Matt. 5:32; 19:9) regarding divorce and remarriage in cases of porneia (“sexual immorality”). The first post presented the views of the earliest Anabaptists, in the 1500s. This current post continues our survey up to the 1860s.

After this post, I’d like to pause my historical survey to attempt a summary of how Anabaptists approached the task of interpreting Jesus’ exception clauses. After that summary, a third historical survey post is in the works, examining how Anabaptist interpretations evolved in the late 1800s to result in an inflexible stance against all divorce and remarriage, with no exceptions.

This series of historical posts springs from an earlier post summarizing how conservative Anabaptists today handle Jesus’ exception clauses.

Introductions aside, let’s resume our historical survey. I have found less evidence for the years 1600 through the 1860s than for the 1500s—probably in part because churches in these centuries sometimes relied on existing documents rather than producing new ones and also partly because historians have tended to focus on the first generations of Anabaptists. But the evidence I’ve found reveals the general pattern of belief quite clearly: Anabaptists in these centuries did not contradict the interpretation of the earliest Anabaptists. Rather, they repeatedly affirmed that Jesus’ exception clauses allow a believer to divorce a spouse who has committed adultery.

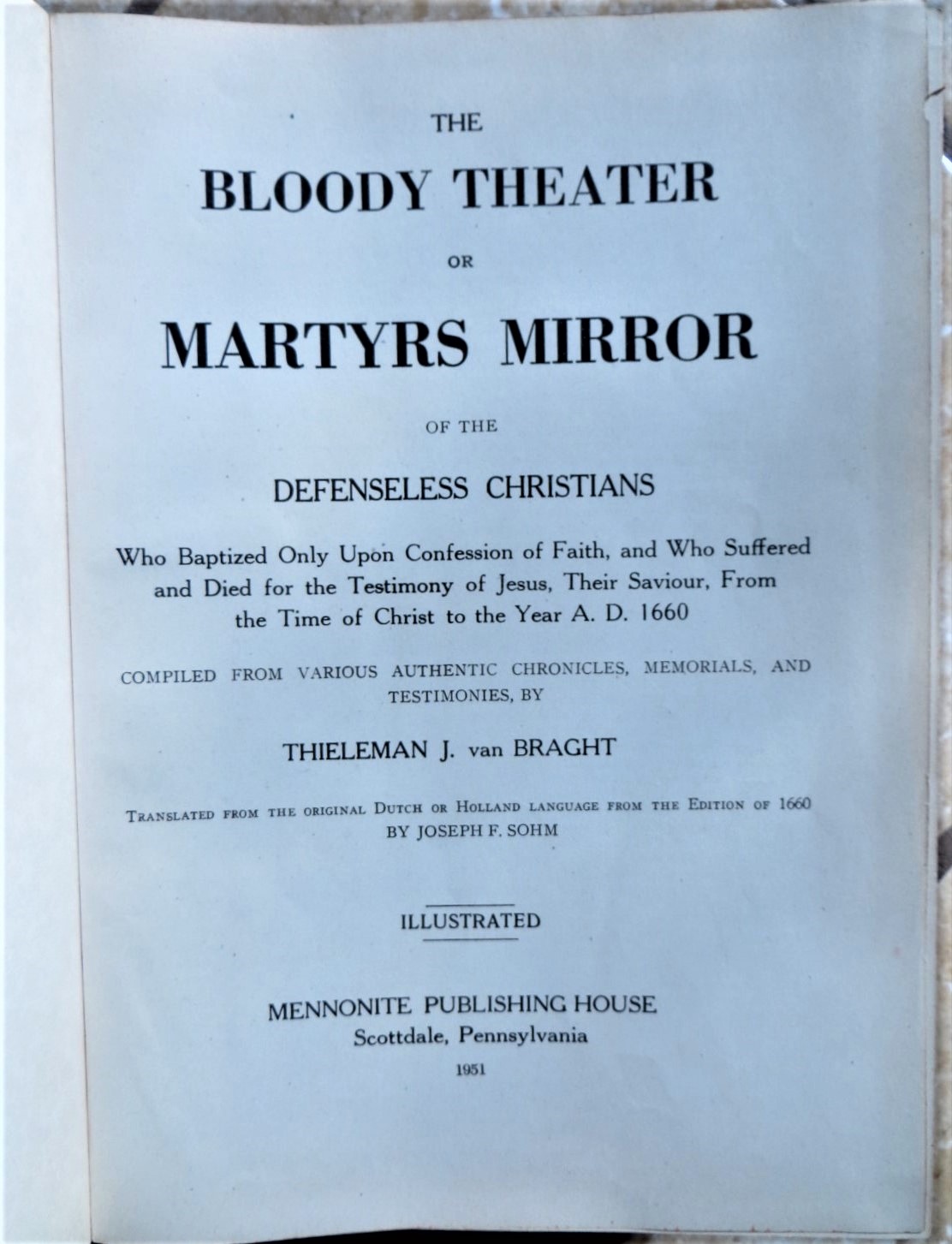

About the year 1600 a “Confession of Faith, According to the Holy Word of God” was written, which was later included by Thieleman J. van Braght in his 1660 compilation Bloody Theatre or Martyrs Mirror. The original authors may have been “two Old Frisian preachers, Sijwaert Pietersz and Peter J. Twisck,” but it “is primarily composed of sentences borrowed from the works of Menno Simons.”1 Its inclusion in the Martyrs Mirror has made it influential. Article XXV of this confession, “Of Marriage,” includes the following excerpt:

Christ as a perfect Lawgiver, rejected and abolished the writing of divorcement and permission of Moses, together with all abuses thereof, referring all that heard and believed Him to the original ordinance of His heavenly Father, instituted with Adam and Eve in Paradise; and thus re-establishing marriage between one man and one woman, and so irreparably and firmly binding the bond of matrimony, that they might not, on any account, separate and marry another, except in the case of adultery or death.2

In 1618 the Dutch Mennonite Hans de Ries, who helped author a couple Waterlanderer confessions I quoted in my last post, wrote another short confession. This one was designed to forge unity with a non-Anabaptist group of Christians who had arrived in Amsterdam after being persecuted as Independents in England. This confession’s brief article on marriage opens with these lines:

We hold marriage to be an ordinance of God, instituted in such manner that every husband shall have his own wife and every wife her own husband. These may not be separated except for reasons of adultery.3

About 1625, Pieter Pietersz of the Waterlander branch of the Dutch Mennonites wrote The Way to the City of Peace, a treatise or allegory written in conversation form which became a sort of statement of faith for the Waterlanderers. In one passage Pietersz rebukes those who taught “that a wife must leave her husband if he has fallen into sin”:

Here they ban innocent women who have not overstepped the law of the Lord, God having commanded that they should not leave their husband, except for adultery, Matt. 19:9; 5:32.4

In 1627 in Amsterdam a confession called “Scriptural Instruction” was drawn up and sent as an “olive branch” to congregations in over half a dozen nearby provinces. This confession was designed to imitate and join the example of Hans de Ries, “who had given much thought and effort to reuniting the discordant and divided body of the Mennonite church in Holland.”5 Evidently the four preachers who drafted this confession thought the following statement on marriage could be affirmed by all Dutch Mennonites:

The marriage of the Children of God… must be… kept inviolate, so that each man shall have his own, only wife, and each wife her own husband; and nothing shall separate them, save adultery. Lev. 18; 20; 1 Cor. 5:1; Matt. 19; Rom. 7:2; 1 Cor. 7:2; Matt. 5:32; 1 Cor. 9:5.6

The Dordrecht Confession of Faith (1632) is the most famous and influential of the old Anabaptist confessions. It includes Article XII, “Of the State of Matrimony.” This article does not mention divorce or remarriage, saying only that “the Lord Christ did away and set aside all the abuses of marriage which had meanwhile crept in.” 7 This language (“abuses,” etc.) mirrors the confession from c. 1600 printed in the Martyrs Mirror (which in turn mirrors earlier Anabaptist writings on the topic) and thus should not be misunderstood as a claim that Christ forbade all divorce.8

The Dordrecht Confession of Faith was included in the Martyrs Mirror (1660). Theileman J. van Braght, the compiler of that volume, shows by his editorial comments that he, too, affirms the historic Anabaptist understanding of Jesus’ exception clause. After describing the martyr John Schut’s belief that a marriage “may not be dissolved, save on account of adultery,” van Braght comments that Schut was “following herein the teaching of Christ. Matt. 19.”9 His inclusion of the c. 1600 confession cited above is additional evidence of his beliefs.

In 1702 Gerhard Roosen, a minister in Hamburg, Germany, produced the first comprehensive Anabaptist catechism in the German language, called Christian Spiritual Conversation on Saving Faith. This became “one of the most popular catechisms among the Mennonites of Europe and America,” with at least twenty-two editions published by 1950.10 The article “On Matrimony” discusses Malachi 2:14-15, Matthew 19:4-9, and 1 Corinthians 7:39 in support of the following conclusion:

Concerning the state of matrimony, Christ made amends for the abuses and decline which had crept into it… Christ also again brought the first state of matrimony to its primitive order… From this [Matt. 19:4-9] it is clearly to be seen, that Christ teaches all christians [sic], that a man (except in case of fornication [Hureren; “whoring”11],) is bound to his wife by the band of matrimony, as long as she lives, and that the wife is also bound to her husband by the same tie as long as he lives.12

Roosen’s book also includes a document called “Brief Instruction: From Holy Scripture, in Questions and Answers, for the Young.” This is actually a reprint of the very first German Anabaptist catechism, which appeared in Danzig, Prussia, in 1690.13 This brief catechism became widely known in English as “The Shorter Catechism.” There the following is found:

Quest. 27. Can also a lawful marriage, for any cause, be divorced [getrennet; “separated”]? Ans. No. For the persons united by such marriage are so closely bound to each other, that they can in no wise separate [scheiden; “divorce”], except in case of “fornication [Ehebruch; “adultery”].” Matt. 19, 9.14

Also in 1702, the Swiss Brethren published an adapted version of the Dordrecht Confession of Faith in their compilation Golden Apples in Silver Bowls. For this book they added the underlined clause below to the article on marriage:

The Lord Christ, too, renounced and swept away all the abuses within marriage which meanwhile had crept in, such as separation, divorce, and entering into another marriage while the original spouse is still living. He referred everything back to the original precept and left it at that (Mt. 19:4-6).15

Does this represent a new, firmer line, rejecting divorce and remarriage even in cases of adultery? It is hard to know. On the one hand, the additional clause certainly strengthens this confession’s stance against the “abuses” of marriage by listing them explicitly. In particular, the rejection of “entering into another marriage while the original spouse is still living” a very clear warning. It is noteworthy that, when these Swiss Brethren chose to add to the original confession, they chose to strengthen the warnings against abuses rather than add a reference to Jesus’ exception clause.

On the other hand, previous confessions had already spoken explicitly against separation and divorce, so such language is not new. Warnings against wrongful remarriage were also previously given, including in the earliest Swiss document on divorce.16 The mere inclusion of these additional comments, then, does not prove the Swiss Brethren had abandoned their understanding of Jesus’ exception clause. After all, the original Dordrecht Confession likewise fails to mention Jesus’ exception clause, yet the historical context of its Dutch Mennonite authors makes it virtually certain that they nevertheless recognized an exception for adultery. For us to confidently state that this adapted confession represents a change in Swiss Brethren thinking, a clear alternative explanation of Jesus’ exception clause would need to be present.

In short, the most we can say for sure is that the Swiss Brethren felt a need to specify what sort of abuses Christ renounced, rather than feeling a need to mention Jesus’ exception clause. Several possibilities could explain this choice, including (a) that they were growing less confident in their historic interpretation of the exception clause or (b) that their historic consensus affirmation of the exception clause was still strong enough that they felt no need to mention it. In support of option (b) is the fact that Roosen’s catechism book (see above) and the Elbing catechism (see below), which both clearly permit divorce in cases of adultery, became very popular from the later eighteenth century on among the Swiss Brethren and their descendants in American (the “Mennonite Church” or “Old Mennonite Church”).17 Given the lack of any similar supporting evidence for option (a), I think option (b) is the better reading of the Swiss Brethren adaptation of the Dordrecht Confession.18

In 1766 a Dutch Mennonite preacher named Cornelis Ris compiled several previous confessions into his own in an attempt to unify the congregations of his time on the “old foundation of the recognized confessions.” His confession, “like the Dordrecht Confession, had only temporary significance in the Netherlands, but attained a true and wide significance outside its home” and was published by the General Conference Mennonite Church as recently as 1906 as its recognized confession.19 The 1904 English printing contains the following excerpt:

The will of God concerning this state is clearly expressed, viz., that only two persons free from all others and not of too close blood relationship may enter into it, to be united and bound together without any reserve even unto death. Matthew 19:5; Ephesians 5:28. The separation of such is moreover, altogether prohibited except for the cause of fornication. Matthew 5:31, 32; 19:7-10; 1 Corinthians 7:10, 11.20

In 1778 a catechism was published at Elbing, Prussia. It is hard to overstate how popular this catechism became among diverse groups of Anabaptists in both Europe and North America, continuing to be used even as recently as the mid-twentieth century.21 It was first translated into English in 1848 and the General Conference authorized a revision of the English translation in 1896. The 1904 printing of this document includes the following question and answer:

May married persons be divorced? No: they shall not be divorced, save for the cause of fornication [Ehebruch; “adultery”]. – Matt. 19:3-9, Matt. 5:22.22

An entry from 1781 in the church register of the Montbéliard Mennonite Church in eastern France (about 7 miles from Switzerland) records an account of remarriage after divorce for adultery:

Today, on November 25, 1781, Christian Lugbüll… and Anna Eicher… wed each other. However, Christian Lugbüll was earlier wed to Anna Blanck…, but [Anna] deserted her husband with great immorality and prostitution, and did not want to tolerate her husband, and the husband, Hans [i.e. Christian] Lugbüll had to take to flight due to her licentious prostitution, and [Anna] then had a bastard more than a year and a day after Hans [i.e. Christian] Lugbüll had left her. Therefore a counsel about this matter was held in Schoppenwihr in Alsace on the 13th of October, 1781, with 24 ministers and it was decided that he could marry again, but Anna Blanck [could] not, because she had committed adultery and not the husband.23

This account is valuable evidence for at least two reasons. First, it shows a Mennonite church of nearly 1800 actually practicing, with official approval, the freedom to remarry that was proclaimed in Anabaptist confessions and catechisms. Second, it shows their practice was similar to that outlined in the Dutch Wismar Articles of 1554, which stated that after adultery the innocent spouse “shall consult with the congregation” and only remarry “subject to the advice of the elders and the congregation.”

I have not been able to find any early North American Mennonite writings that discuss Jesus’ exception clauses. There is good reason, however, not to read this silence as a rejection of the historic Anabaptist position.

In 1804 a small book was published in Pennsylvania by a bishop named Christian Burkholder. An enlarged reprint published later that year carried the signatures of twenty-seven ministers of the Lancaster Mennonite Conference and “was probably adopted as an official church edition.”24 The book went through at least eight German and five English editions during the nineteenth century. It was first translated into English in 1857, with title “Useful and Edifying Address to the Youth,” when it was included as Part IV in Roosen’s Christian Spiritual Conversation on Saving Faith.

This book includes a brief discussion of marriage. There is no mention of Jesus’ exception clause, but near the end of the discussion we read this: “Further I would recommend you to consider the 12th article in our small Confession of Faith, and the 25th in the large one.” The references are almost certainly to the Dordrecht Confession of Faith (“small”) and the confession from c. 1600 (“large”; see above).25 The Dordrecht Confession was “the first Mennonite book printed in America” (in 1727),26 and both of these confessions were included in the Martyrs Mirror, which was translated into German and published in the Ephrata Colony in 1748.

What is important for our discussion here is that Burkholder’s book demonstrates that American Mennonites in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century were directing their members to the large confession of c. 1600, which states that a husband and wife may “not, on any account, separate and marry another, except in the case of adultery or death.”

Even apart from this explicit comment in Burkholder’s book, we know from publication data that from early colonial times up through the nineteenth century and beyond North American Mennonites were actively publishing, translating, and using multiple European Mennonite documents that taught the historic Anabaptist interpretation of Jesus’ exception clauses.

For example, in 1837 the prominent Virginia bishop Peter Burkholder, together with translator Joseph Funk, published an English edition of the c. 1600 large confession, as well as “The Shorter Catechism” (originally pub. 1690). In Funk’s translation the latter includes this question and answer:

Q. 27. Can the bonds of an orderly regular marriage be broken for every cause?

A. No : for they are united and bound together with ties of the most tender obligations and engagements, so that in no case they may part asunder, except it be for the cause of fornication. Matth. 5: 32.27

Many more such republications occurred. Here is a list of North American republication dates for some relevant documents:28

- Menno Simon’s Foundation of Christian Doctrine: In German: 1794, 1835, 1849, 1851, 1853, and 1876. In English: 1835, 1863, 1869.

- Martyrs Mirror: In German: 1748, 1814; 1848-49; 1849; 1870; 1915. In English: 1748-49; 1837; 1886; 1938.

- Roosen’s catechism, Christian Spiritual Conversation on Saving Faith: In German: 11 editions (1769-1950). In English: 5 editions (1857-1950).

- Elbing catechism: In German: 1824, etc. In English: 1848, etc.

- Confession of Cornelis Ris: In German, 1904, 1906. In English: 1850, 1895, 1902, 1904.

It is also true, of course, that Mennonite immigrants brought European copies of these documents to American and used them there long before they republished them. The fact that they republished them shows that these documents, and the teachings they contained, were important to early Mennonite generations in North America.

Our chronological journey takes us next to 1853 in South Russia, where the Church in Rudnerweide in Odessa published a “Confession or Short and Simple Statement of Faith of Those Who are Called the United Flemish, Frisian, and High German Anabaptist-Mennonite Church.” This confession quotes emphasizes the strength of the marriage covenant or “bond of matrimony”:

In matrimony man and wife are so bound together and mutually obligated that for no reason and for no cause whatever may they be parted from each other, except for fornication and adultery, even as we read concerning this in the evangelist Matthew, where the Pharisees and Sadducees came to Christ, tempted Him and said, “Is it right that a man should be divorced from His wife for any cause?” …He said to them, “…Whoever divorces his wife, except for causes of fornication, and marries another, he breaks the marriage bond and he who marries a person who has been divorced also breaks the marriage bond.” From this it may be clearly seen and understood that the bond of matrimony is a firm indissoluble bond which may not be broken nor may the parties be divorced from each other except for cause of fornication, even as the Lord Christ said.29

The previous confession raises the question of what Bible translations were used by early Anabaptists. Where our English versions quote Jesus as saying that the one who wrongfully divorces and remarries “commits adultery,” this confession says “breaks the marriage bond.” This phrase probably means “violates the marriage covenant,”30 which accurately expresses the central idea of what it means to “commit adultery.” This wording almost certainly is borrowed from Luther’s translation.31 I will return to this question of Bible translations later.

1864 marked the beginning of a new era for the Mennonite Church in North America.32 In January of that year, John F. Funk published the first issue of a new periodical that would track and shape the thinking of Mennonites for nearly half a century: the Herald of Truth. Funk was not the first Mennonite publisher in America,33 but his publishing efforts were so prolific and his influence so large that he has been called “more than any one leader the founder of the publication and mission work of the Mennonite Church” and “the most important figure in the life of the Mennonite Church in the nineteenth century.”34 Funk’s paper would document and enable many important conversations among Mennonites, including debates about divorce and remarriage.

The first clear evidence that I have found of Mennonites who disagreed with the historic Anabaptist interpretation of Jesus’ exception clause comes from an 1867 issue of Herald of Truth.35 I plan to begin my next historical survey post with that story.

I’ll end this post, however, with the earliest reference to divorce that I found in this periodical, from February, 1865:

I cannot find anywhere in the Scriptures that husband and wife are permitted to separate from [scheiden; “divorce”] each other, except in case of fornication [Hurerei; “whoring”]; and even then they are at liberty to do as they choose, to separate [scheiden; “divorce”], or not…36

The way that this author expresses his interpretation of Jesus’ exception clause is telling. His offhand manner suggests that he was confident his interpretation was shared by many of his readers; if a spouse was sexually promiscuous, their husband or wife was permitted to divorce.37

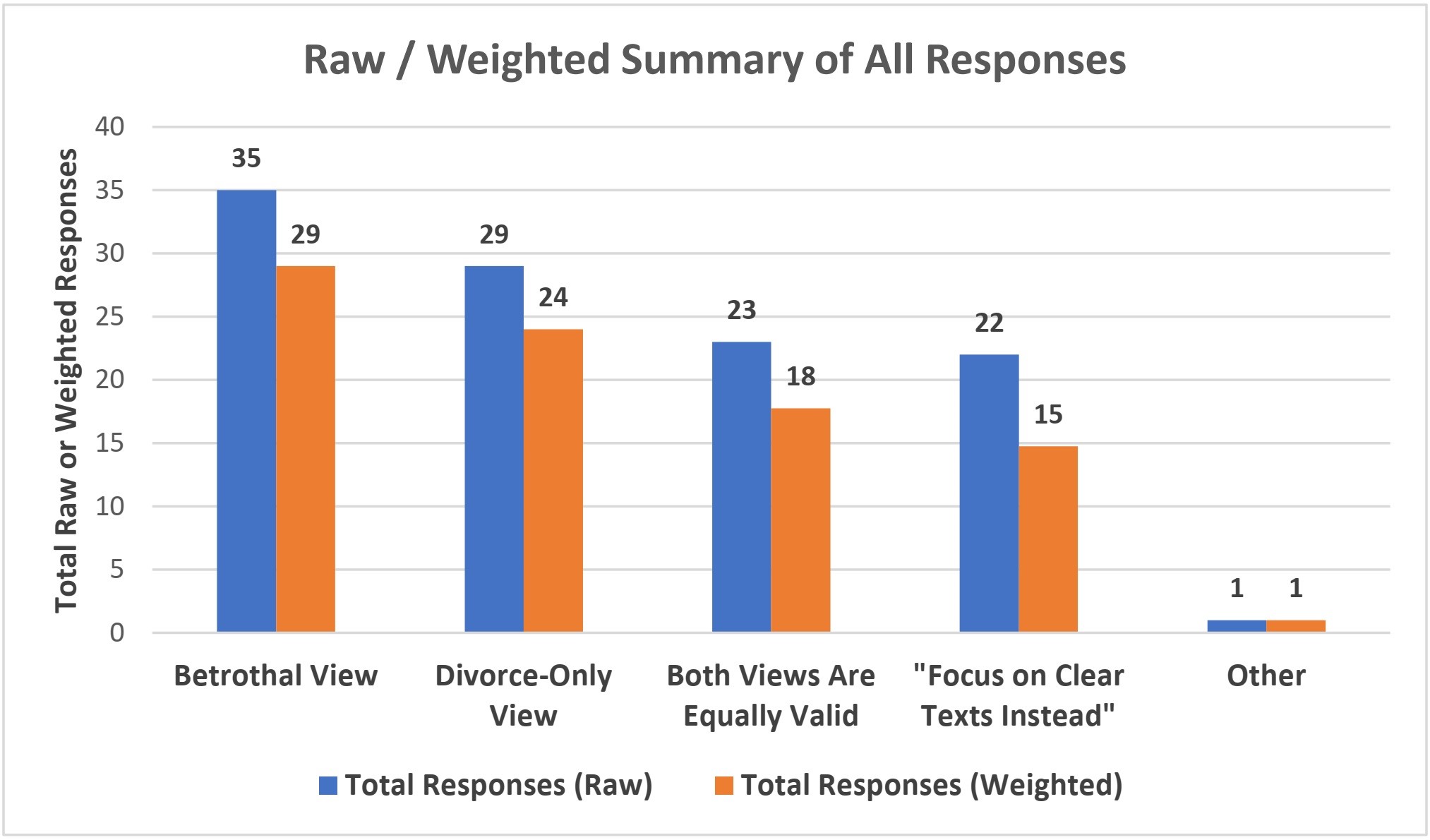

How should we summarize the evidence from 1600 to the 1860s? Did Anabaptists in these centuries continue to understand Jesus’ exception clauses as their forebears did?

In support of a Yes answer are the following facts:

- I have not found any Anabaptist writing from this period that explicitly contradicts the early Anabaptist interpretation of Jesus’ exception clauses. Some speak against divorce without mentioning Jesus’ exception clause at all, but none offers an alternative interpretation of Jesus’ words.

- Anabaptist writings from the 1500s that affirmed both divorce and remarriage in cases of adultery or fornication continued to be republished without revision and used widely during this period.

- Multiple new writings from this period (at least ten quoted above) explicitly mention an exception for divorce in cases of adultery or fornication, including several catechisms which gained wide usage.

Three facts should be considered in support of a No answer, however:

- The latest document quoted above that explicitly affirms that remarriage is permitted in cases of adultery is the oldest one quoted in this post—the confession from c. 1600 that was included in the Martyrs Mirror. Probably many (all?) of the authors of these documents assumed that remarriage was permitted alongside divorce.38 But, except for the c. 1600 confession, the documents above explicitly mention only divorce when citing Jesus’ exception clause.

- The confession that was most widely used during this period, the Dordrecht Confession, makes no mention of Jesus’ exception clause, and thus did not reinforce the historic Anabaptist interpretation of his words for the generations of Anabaptists who used it.

- As I mentioned above, there is explicit evidence that in the 1860s some members of the Mennonite Church thought remarriage was wrong in cases of adultery and, further, that they affirmed separation but not actual divorce. Such views may have begun decades or more before Funk’s paper preserved them for our discovery.

Despite these important qualifications, the following reality remains highly significant:

From what I can discover, no extant Anabaptist writings from 1600 until the 1860s deny that Jesus’ exception clause permits both divorce and remarriage in cases of adultery. All documents either affirm this historic Anabaptist interpretation as part of what is “clearly to be seen” or do not address the question at all.39

This is very striking because, within fifty years, it would be commonplace for North American Mennonite writings to deny that Jesus’ exception clause permits either remarriage or divorce.

It often takes time for theological beliefs to change, and changes in official church positions take even longer. I hope to explore the contours and possible causes of these changes in a future post.

But first, I’d like to consider how early Anabaptists went about the task of interpreting Jesus’ exception clauses. Where did they begin? How did they synthesize these clauses with other biblical texts? Did they do this well? Did they make mistakes? Do they have things to teach us? I welcome your prayers as I ponder these questions.

What strikes you most about the evidence from the period 1600 through the 1860s? How should we assess both the continuity of belief and the subtle hints of change? Are you aware of historical evidence or dynamics that I should add to my evaluation? I welcome your comments below—and thanks for reading!

If you want to support more writing like this, please leave a gift:

- “The Confession of Faith (P.J. Twisck, 1617),” Global Anabaptist Wiki, “initiated by the Mennonite Historical Library at Goshen College,” last modified March 24, 2016. https://anabaptistwiki.org/mediawiki/index.php?title=The_Confession_of_Faith_(P.J._Twisck,_1617) ↩

- “Confession of Faith, According to the Holy Word of God,” The Bloody Theater of Martyrs Mirror of the Defenseless Christians, ed. Theileman J. van Braght, trans. Joseph. F. Sohm (Scottdale, PA: Mennonite Publishing House, 1951), 401. Emphasis added. Available online: https://anabaptistwiki.org/mediawiki/index.php?title=The_Confession_of_Faith_(P.J._Twisck,_1617) ↩

- Hans de Ries, “Short Confession of Faith and the Essential Elements of Christian Doctrine,” 1618; “A Short Confession of Faith by Hans de Ries (1618),” trans. Cornelius J. Dyck, Global Anabaptist Wiki, “initiated by the Mennonite Historical Library at Goshen College,” last modified March 24, 2016. https://anabaptistwiki.org/mediawiki/index.php?title=A_Short_Confession_of_Faith_by_Hans_de_Ries_(1618). Emphasis added. From Cornelius J. Dyck, “A Short Confession of Faith by Hans de Ries,” Mennonite Quarterly Review 38 (January 1964): 5-19. ↩

- Pieter Pietersz, The Way to the City of Peace, Spiritual Life in Anabaptism, trans. and ed. by Cornelius J. Dyck (Scottdale, PA: Herald Press, 1995), 267. Emphasis added. ↩

- Christian Neff and Nanne van der Zijpp, “Olive Branch Confession (1627),” Global Anabaptist Wiki, “initiated by the Mennonite Historical Library at Goshen College,” last modified March 24, 2016. https://anabaptistwiki.org/mediawiki/index.php?title=Olive_Branch_Confession_(1627) ↩

- “Scriptural Instruction,” The Bloody Theater of Martyrs Mirror of the Defenseless Christians, ed. Theileman J. van Braght, trans. Joseph. F. Sohm (Scottdale, PA: Mennonite Publishing House, 1951), 32; also 27. Emphasis added. Available online: https://anabaptistwiki.org/mediawiki/index.php?title=Olive_Branch_Confession_(1627) ↩

- Here is the entire Article XII: “We confess that there is in the church of God an honorable state of matrimony, of two free, believing persons, in accordance with the manner after which God originally ordained the same in Paradise, and instituted it Himself with Adam and Eve, and that the Lord Christ did away and set aside all the abuses of marriage which had meanwhile crept in, and referred all to the original order, and thus left it. Genesis 1:27; Mark 10:4. In this manner the Apostle Paul also taught and permitted matrimony in the church, and left it free for every one to be married, according to the original order, in the Lord, to whomsoever one may get to consent. By these words, in the Lord, there is to be understood, we think, that even as the patriarchs had to marry among their kindred or generation, so the believers of the New Testament have likewise no other liberty than to marry among the chosen generation and spiritual kindred of Christ, namely, such, and no others, who have previously become united with the church as one heart and soul, have received one baptism, and stand in one communion, faith, doctrine and practice, before they may unite with one another by marriage. Such are then joined by God in His church according to the original order; and this is called, marrying in the Lord. 2 Corinthians 7:2; 1 Corinthians 9:5; Genesis 24:4; Genesis 28:2; 1 Corinthians 7:39.” “Dordrecht Confession of Faith (Mennonite, 1632),” Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. 1632. Accessed June 17, 2020. https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Dordrecht_Confession_of_Faith_(Mennonite,_1632)#XII._Of_the_State_of_Matrimony ↩

- Over two-thirds of this brief article focuses on a primary concern of early Anabaptists, that an “honorable state of matrimony” consists of “two free, believing persons” (emphasis added) and that Christians must marry only “in the Lord.” Another confession from 1630 that is included in Martyrs Mirror likewise devotes over half of the space of its marriage article to the importance of marrying only a believer, without any mention of divorce. In addition, it contains another lengthy portion (about three times the length of its marriage article) that discusses church discipline in cases when a believer marries an unbeliever (“Confession of Faith,” The Bloody Theater of Martyrs Mirror of the Defenseless Christians, ed. Theileman J. van Braght, trans. Joseph. F. Sohm (Scottdale, PA: Mennonite Publishing House, 1951), 36-37). The 1627 confession cited above also devotes nearly its marriage article to marrying “only in the Lord.” Such evidence illustrates how, for early Anabaptists, marriage between a believer and an unbeliever was a much more urgent point of debate and concern than the topic of divorce after adultery. ↩

- “John Schut, A.D. 1651,” The Bloody Theater of Martyrs Mirror of the Defenseless Christians, ed. Theileman J. van Braght, trans. Joseph. F. Sohm (Scottdale, PA: Mennonite Publishing House, 1951), 654. ↩

- Robert Friedmann, “Christliches Gemütsgespräch (Monograph),” Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. 1953. Web. July 12, 2020. https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Christliches_Gem%C3%BCtsgespr%C3%A4ch_(Monograph)&oldid=155562 ↩

- The English translations of some of these documents appear to be rather loose. I will add alternative translations in brackets for some key words, also providing the original German word. (I used this online dictionary to help me understand the German terms and also ran phrases through Google Translate.) In this case, I am not certain of the part of speech of Hureren, but the family of words clearly refers to “whoring,” not premarital sex. The German original for this passage can be found on page 124 of this scanned book: https://www.google.com/books/edition/_/397qR_AMjOQC?hl=en&gbpv=1 ↩

- Gerhard Roosen, Christian Spiritual Conversation on Saving Faith, for the Young, in Questions and Answers, and a Confession of Faith of the Mennonites (Lancaster, PA: John Baer and Sons, 1857), 108-109. Emphasis added. Available online: https://archive.org/details/christianspiritu01menn/page/108/mode/2up ↩

- Christian Neff and Harold S. Bender, “Catechism,” Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. 1953. Web. July, 2 2020. https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Catechism&oldid=162939 ↩

- Roosen, ibid., 147. Emphasis added. Bontrager says that “a rigid view” of divorce and remarriage “was taken from 1690 to 1800” (G. Edwin Bontrager, Divorce and the Faithful Church (Scottdale, PA: Herald Press, 1978), 104). He gives no evidence or additional comment for this assertion, but it seems likely that his starting date is an allusion to this “Shorter Catechism.” Does this catechism present a “rigid view”? The English translation could suggest so; after all, the question is about whether “divorce” is permitted, the answer is “no,” and the follow-up statement only offers permission to “separate.” However, the original German question asks about whether a marriage can wiederum getrennet werden, and the answer uses the word scheiden. While both terms can mean “separate,” it appears that the former term is a more general reference to separation (or “splitting up”), while the latter term is more often explicitly a reference to divorce. Further, the word translated “fornication” above is Ehebruch, which is more accurately translated “adultery” (or, in a translation that reflects etymology, “marriage-breaking”). In summary, it appears to me that a more careful translation of the original German would read like this: “Can also a lawful marriage, for all sorts of reasons, be separated? Ans. No. For the persons united by such marriage are so closely bound to each other, that they can in no wise divorce, except in case of adultery.” This reading hardly indicates a more “rigid view” than that of the early Anabaptists. (Note: I found the original German catechism question here: https://www.google.com/books/edition/_/397qR_AMjOQC?hl=en&gbpv=1&bsq=eine%20ordentliche. ↩

- “Christian Confession of Faith Of the Peace-Loving And Distinguished Christians Who are called Mennonites,” trans. Elizabeth Bender and Leonard Gross, Golden Apples in Silver Bowls, ed. Gross (Lancaster, Pa.: Lancaster Mennonite Historical Society, 1999), 252. ↩

- “And he who separates or permits to separate except for the one cause of fornication, and changes {companions}, commits adultery. And he who marries the one divorced causeth her to commit adultery… We declare that when a man or woman separates except for fornication (that is, adultery), and takes another wife or husband, we consider this as adultery and the participants as not members of the body of Christ, yea, he who marries the separated one we consider a fornicator” (“Concerning Divorce,” c. 1525-1533). This document explicitly mentions all three abuses listed in the 1702 expanded confession: separation, divorce, and marrying another. ↩

- Christian Neff and Harold S. Bender, “Catechism,” Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. 1953. Web. July 10, 2020. https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Catechism&oldid=162939 ↩

- In a recent article, Andrew V. Ste. Marie cites this adapted confession as evidence that a firm stance against all divorce and remarriage (no exceptions) was not a new idea in the time of Daniel Kauffman: “Among the Mennonites whose origins could be traced to the Swiss Brethren Anabaptist tradition, the roots of the diversity in the discussion on divorce and remarriage go all the way back to the sixteenth century. A tract from the first generation of Swiss Brethren titled On Divorce argues that adultery is grounds for divorce and the innocent party may remarry. The Swiss Anabaptist Short Simple Confession from 1572 argues for the same position. However, even in Europe, there is evidence of another view. The modified version of the Dordrecht Confession printed in the Swiss Brethren devotional book Golden Apples in Silver Bowls in 1702 teaches… {The same quote I provided above.} Jacob Stauffer, founder of the “Stauffer” or Pike Mennonites, also expressed a stricter view, writing c. 1850 that ‘the covenant of marriage cannot and dare not be broken to marry another except through natural death.’ Thus, the roots of the multiple views on divorce and remarriage go all the way back to Europe in the Swiss Brethren experience.” (“Research Note: Nineteenth-Century Mennonites Deal With Divorce and Remarriage,” Mennonite Quarterly Review 94 (April 2020), 249.) It seems to me that Ste. Marie overstates his evidence here in two ways. First, he does not consider other possible ways to understand the Swiss Brethren additions to the Dordrecht Confession, as I have done above. (In fact, he is somewhat misleading in failing to clarify that most of quotation he provides was actually part of the original document.) Second, even if this adapted confession should be understood to outlaw all divorce and remarriage, with no exceptions, this still provides evidence of “diversity in the discussion on divorce and remarriage” only as early as the eighteenth century, not “the sixteenth century.” Despite my disagreements on these points, I found much of the rest of Ste. Marie’s article helpful and am grateful he mentioned it to me. ↩

- “Mennonite Articles of Faith by Cornelis Ris (1766),” Global Anabaptist Wiki, “initiated by the Mennonite Historical Library at Goshen College,” last modified March 24, 2016. https://anabaptistwiki.org/mediawiki/index.php?title=Mennonite_Articles_of_Faith_by_Cornelis_Ris_(1766) ↩

- Cornelis Ris, Mennonite Articles of Faith as Set Forth in Public Confession of the Church: a Translation (Berne, IN: Mennonite Book Concern, 1904). Emphasis added. Available online: https://anabaptistwiki.org/mediawiki/index.php?title=Mennonite_Articles_of_Faith_by_Cornelis_Ris_(1766)#XXXI._Of_Marriage ↩

- “This catechism… became not only the catechism of the Amish in America, but also of the Mennonite Church (MC), the General Conference Mennonite Church, the Evangelical Mennonite Brethren (now Fellowship of Evangelical Bible Churches), and the Kleine Gemeinde (now called Evangelical Mennonites). It is nothing short of astounding to discover that the Elbing-Waldeck catechism became the standard source of doctrinal, prebaptismal instruction for such widespread groups as the American groups just listed, the Mennonites of Russia (except the Mennonite Brethren group 1860ff.), those of West Prussia, and those of France; further that it is still in widespread use in North America wherever catechisms are used, in both English and German; and finally, that no other catechism, except the much larger and somewhat different Gemüthsgespräch — and that only among the Mennonite Church (MC) of Eastern Pennsylvania — has ever successfully competed with it in any language in these countries” (Christian Neff and Harold S. Bender, “Catechism,” Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. 1953. Accessed June 17, 2020. https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Catechism&oldid=162939). ↩

- The Catechism or Simple Instruction From the Sacred Scriptures, as Taught by the Mennonite Church (Berne, IN: Mennonite Book Concern, 1904). Emphasis added. Available online with an introduction: https://anabaptistwiki.org/mediawiki/index.php?title=Elbing_Catechism_(Mennonite,_1778). German version available here: https://archive.org/details/katechismusoderk00elbi_7/page/48/mode/2up ↩

- Montbéliard Mennonite Church Register: 1750-1958, trans. and ed. by Joe A. Springer (Goshen, IN: Mennonite Historical Society, 2015), p. 147. Emphasis added. https://dwightgingrich.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Montbeliard-Church-France-Divorce.pdf. I am grateful to Joe Springer for alerting me to this account. ↩

- Ira D. Landis, and Robert Friedmann, “Burkholder, Christian (1746-1809),” Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. 1953. Web. July 12, 2020. https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Burkholder,_Christian_(1746-1809)&oldid=143506 ↩

- I did not find any other confession that has a 25th article on marriage, and the only other one I found having a 12th article on marriage is the Strasbourg Discipline from 1568 (https://anabaptistwiki.org/mediawiki/index.php?title=Strasbourg_Discipline_(South_German_Anabaptist,_1568)), a document with far less historical importance. ↩

- John A. Hostetler, God Uses Ink: The Heritage and Mission of the Mennonite Publishing House After Fifty Years (Scottdale, PA: Herald Press, 1958), 9. ↩

- “Extract from the Catechism,” The Confession of Faith, of the Christians Known by the Name of Mennonites, in Thirty-Three Articles; With a Short Excerpt from Their Catechism, trans. Joseph Funk (Winchester: Robinson & Hollis, 1837), 431. https://archive.org/details/confessionoffait00menn/page/430/mode/2up. See here for more background information: https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Burkholder,_Peter_(1783-1846). Interestingly, in this Funk translation of the c. 1600 confession, the possibility of remarriage after divorce for adultery is not explicitly mentioned: “so inseparably joined and bound together that nothing but death or adultery shall part and seperate {sic}” (p. 211). Joseph F. Sohm’s careful 1886 translation (see above) is probably more accurate: “so irreparably and firmly binding the bond of matrimony, that they might not, on any account, separate and marry another, except in the case of adultery or death.” ↩

- I have made no attempt to be exhaustive. Documentation for these dates can be found on GAMEO.com or in God Uses Ink (Hostetler, ibid.). ↩

- “Confession, or Short and Simple Statement of Faith (Rudnerweide, Russia, 1853),” trans. Peter J. Klassen, Global Anabaptist Wiki, “initiated by the Mennonite Historical Library at Goshen College,” last modified March 24, 2016. https://anabaptistwiki.org/mediawiki/index.php?title=Confession,_or_Short_and_Simple_Statement_of_Faith_(Rudnerweide,_Russia,_1853). Emphasis added. Quotation marks and spelling of “Sadducees” corrected for clarity. This confession was adopted by a congregation in Oregon in 1878 and also reprinted a couple times in the late 1800s in Elkhard, Indiana–once for use by a church in Turner County, South Dakota and once by an elder of the Evangelical Mennonite Brethren. ↩

- It may be incorrect to interpret the phrase as “ends the marriage” although violating the marriage covenant certainly puts the marriage itself in question. ↩

- It is probable that the other confessions I have quoted in my historical survey likewise used Bible versions shaped by Luther’s translation. It is common for English translators of historical documents to simply use a common English translation such as the KJV whenever Bible quotations occur, rather than directly translating from the historical document. This can make it difficult to trace how the authors of historical documents were influenced by the translations they used. In this case of this confession, it appears Klassen translated biblical quotations directly from the German text of the confession, rather than substituting any existing English translation. ↩

- For an historical overview of this largest of the American Mennonite groups, see: Harold S. Bender and Beulah Stauffer Hostetler, “Mennonite Church (MC),” Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. January 2013. Web. July 13, 2020. https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Mennonite_Church_(MC)&oldid=167350 ↩

- Henry Funk in Pennsylvania (d. 1760), Joseph Funk in Virginia (1778-1862), and Benjamin Eby in Ontario (1785-1853) were important predecessors—two of them being relatives! None of these, to my limited knowledge, published anything on divorce that I have not mentioned in this post. ↩

- Cornelius J. Dyck, An Introduction to Mennonite History, 2nd ed. (Scottdale, PA: Herald Press, 1981), 220, 217. ↩

- Andrew V. Ste. Marie writes that “Jacob Stauffer, founder of the “Stauffer” or Pike Mennonites, also expressed a stricter view, writing c. 1850 that ‘the covenant of marriage cannot and dare not be broken to marry another except through natural death’” (Ste. Marie, Ibid., 249, quoting from A Chronicle or History Booklet About the So-Called Mennonite Church, trans. Amos Hoover (Lancaster, PA: Lancaster Mennonite Historical Society, 1992), 186). Ste. Marie may be correct that Jacob Stauffer did not understand Jesus’ exception clause to provide any permission for divorce or remarriage; I have not been able to check the context of this quote to get a clearer sense of what Stauffer may have meant. At any rate, Stauffer’s statement is less than twenty years older than the 1867 Herald of Truth article, so the historical picture is similar either way. ↩

- “Answer to ‘A Brother’s Question,’” Herald of Truth, Vol. 2, No. 2, 11, https://archive.org/details/heraldoftruth02unse/page/n6/mode/1up This sentence occurs in the context of the writer arguing against a husband and wife shunning each other in cases of church discipline. ↩

- In coming decades Mennonites would increasingly draw a distinction between divorce and mere separation, but I don’t think such a distinction is intended here. In this sentence the word translated “separate” (twice) appears in the German (in Der Herold der Wahrheit, the German twin publication to Herald of Truth; see here) as scheiden, which is a word that is regularly used to refer to divorce, not merely informal separation. (See footnote to “Shorter Catechism” above for more discussion of this word.) In place of the word “fornication,” the German text has Hurerei; “whoring,” thus referring not to premarital sex but to sexual promiscuity. ↩

- Some arguably imply as much, given the way they cite or quote Jesus’ exception clauses and given the prior Anabaptist interpretation of those clauses. For example, Roosen’s 1702 catechism quotes Jesus’ words about both divorce and remarriage (Matt. 19:9) immediately before offering the following commentary: “From this it is clearly to be seen, that Christ teaches all christians, that a man (except in case of fornication,) is bound to his wife by the band of matrimony, as long as she lives…” This suggests that “bound to his wife” means “not free to divorce and remarry,” which suggests that “in case of fornication” a man would be free to do both. ↩

- Of course, it is possible I have missed important evidence, for (a) I am not formally trained in Anabaptist historical study, (b) I do not have physical access to any Mennonite archives, and (c) I do not read German. If I have missed evidence, I am eager to update my post and adjust my conclusions as needed. That said, I have seen nothing in primary or secondary literature to suggest that my conclusions here are inaccurate. It appears to me that, even if contradictory evidence were found, it would only offer an exception to the rule, which would still stand. ↩