This post continues my series on Jesus, divorce, and remarriage, where I examine Jesus’ words with a focus on this question: Did Jesus believe that marriage is indissoluble? Here are my posts so far:

Jesus on Divorce and Remarriage: Introduction (JDR-1)

Hyper-Literalism, Could vs. Should, and a Guiding Question (JDR-2)

“Cleave” Does Not Imply an Unbreakable Bond (JDR-3)

“One Flesh” Does Not Imply an Unbreakable Bond (JDR-4)

“God Has Joined Together” Does Not Imply an Unbreakable Bond (JDR-5)

Genesis 2:24 as God’s Creation Norm for Marriage (JDR-6)

Summary of this post: I ask whether Jesus meant “let not man separate” or “let not man try to separate,” as some propose. Based on clues from literary and historical contexts, I argue that Jesus’ first listeners understood him to be prohibiting the full dissolution of marriage—and that Jesus expected to be understood this way. I note that some proponents of marriage indissolubility acknowledge such a conclusion is reasonable, yet point ahead to Jesus’ statement about remarriage being “adultery” as proof that marriage is indissoluble. I promise to address this statement and acknowledge some complexities of this divorce discussion.

Before I jump into today’s post, I feel I should clarify some potential misunderstandings about my goals in this series:

- If you are confused about my purposes or beliefs, please read my post promoting radical faithfulness in marriage.

- I’m trying to choose my post titles carefully. When I say a certain expression “does not imply an unbreakable bond,” I do not necessarily mean “implies a breakable bond.” Similarly, when I say “implies a breakable bond” in today’s post, I definitely do not mean “proves a breakable bond.” That said, after a while, enough non-implications plus implications do add up to a beyond-all-reasonable-doubt sort of proof. I’m definitely not there yet, though, in this series, so thank you for not saying I’ve claimed something I’ve not yet claimed!

- I’m somewhat conflicted about naming and quoting people that I’m disagreeing with, especially when I know them personally. I’ve been on the receiving end of enough critique to know that public critique—even when it is respectful and perhaps especially from friends—can be uncomfortable and even potentially debilitating. I’m also aware it is easy to be misunderstood and that none of us still agrees with everything we’ve ever said or taught in public. That said, (a) it is standard, respectful academic procedure to sharpen thinking by quoting and evaluating the public teachings of others, (b) such public discussion of the public teachings of others seems consistent with the NT’s picture of the greater accountability expected of church leaders, and (c) for the purposes of my series it seems that direct quotations will help some readers better understand the significance, within the conservative Anabaptist context, of the questions I am discussing.

Please know I have a lot of respect for many of the people I’m quoting and disagreeing with in this series! Many of them, to paraphrase Jesus’ parable (Matt. 13:23), are bearing gospel fruit thirtyfold and sixtyfold, compared to my own tenfold (on a good day).

If I quote you in this series and you think I’m misunderstanding you or quoting something you no longer affirm, please let me know. I will be happy to do my best to correct any misrepresentations. I hope we can learn from each other, and I sincerely wish you God-speed in your kingdom work and worship.

Thank you for reading these clarifications. And now… on to today’s post!

Introduction: Should Not or Cannot Separate?

“Let not man separate” is the command that Jesus gives after summarizing the union that God designed for husbands and wives (Matt. 19:6). Since it is God who has joined a husband and a wife, separating marriages is a sin against God, not merely against humans.

This clause “let not man separate” offers a classic illustration of how Bible readers can get confused between the “should” and “could” of Scripture. The most obvious way to Jesus’ command is that he is saying humans should not do something that they could do. As commentator R. T. France noted, “the argument here is expressed not in terms of what cannot happen, but of what must not happen: the verb is an imperative: “let not man separate.”[1]

Bible teachers who believe marriage is indissoluble are often discontent with that simple reading, however.

John Piper, for example, waffled in his comments on this verse. First, he gave this summary: “Jesus… says that none of us should try to undo the ‘one-flesh’ relationship which God has united.” But later, citing this same statement of Jesus, Piper said “only God, not man, can end this one-flesh relationship.”[2] So which is true? Man should not separate, or man cannot separate?

To be fair, Piper’s two statements are indeed consistent with each other—but only because Piper added “try to” to Jesus’ prohibition on separating husbands and wives. Is this fair? Did Jesus mean “let not man separate,” as his words are recorded? Or did he actually mean “let not man vainly try to separate” or perhaps “imagine they have separated”?

How Did Jesus Expect to be Understood?

How would Jesus’ hearers have understood him? I see at least four reasons why Jesus’ hearers would have understood him to be implying that a marriage can, indeed, be dissolved.

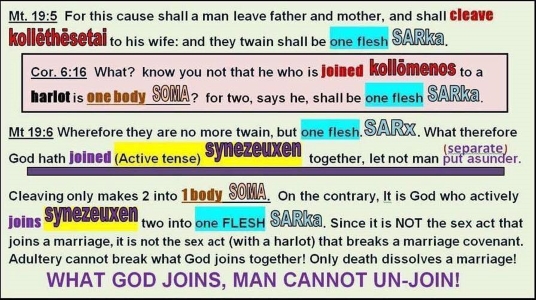

First, nothing Jesus has said so far suggests that marriage is indissoluble. Remember, when Jesus says we are not to separate “what God has joined,” he is pointing back to what he just said—that God made humans “male and female” and therefore a man shall “hold fast” to his wife and they shall become “one flesh.” As noted in previous posts, none of this language implies that marriage involves an unbreakable bond. To the contrary, all this language was used elsewhere to refer to bonds that can be broken. This suggests that there is a real possibility that “what God has joined” could be “separated.”

Second, the words joined and separated are virtual opposites, and the way Jesus paired them reinforces the idea that they should be understood that way. For example, I could say, “I’m sleeping, so stop talking,” and we could debate whether talking has the potential to undo my sleeping or whether talking has some other possible effect that concerns me. But if I say, “I’m sleeping, so don’t wake me up,” then it is clear: waking me up will end my sleeping! (Let’s not get distracted about why I’m talking in my sleep.) Similarly, Jesus’ direct pairing of the opposite terms joined and separated puts the burden of proof on anyone who argues that the latter does not undo the former.

Third, in no other case, to my knowledge, does Jesus forbid humans from doing something that is actually impossible to do. I’ve actually looked, and I can’t find such an example. The closest, perhaps, might be this: “When you give to the needy, do not let your left hand know what your right hand is doing” (Matt. 6:3). On a literal level, true, it is impossible for your left hand to know what your right hand is doing! But that statement uses obvious hyperbole and is thus very different from Jesus’ straightforward command against separating what God has joined. On a practical level, there is nothing hyperbolic whatsoever about the possibility of separating a husband and a wife. It is a possible, common event.

Fourth, Jesus was engaging Jews on a question about divorce, and virtually everyone at the time—Jews and Greco-Romans alike—understood that divorce completely dissolved a marriage, freeing one for remarriage. “Is it lawful to divorce one’s wife for any cause?” was the question. “What God has joined together, let not man separate” was Jesus’ answer. Significantly, Jesus’ term “separate” (χωρίζω) was frequently used in both informal and legal contexts at the time to refer to divorce. True, it can have a more general meaning, and it probably does carry broader implications here. But Jesus’ hearers would certainly have heard it as referring most directly to divorce—thus, in their understanding, obviously referring to the full dissolution of a marriage.

Judging by these four reasons, Jesus’ command to not separate strongly implies that marriage is not an unbreakable bond. His listeners heard him clearly imply that marriage can indeed be dissolved by humans. What is more, Jesus, as a fellow Jew and a master teacher, knew that his listeners would understand him this way. In short, Jesus was using ordinary words in ordinary ways to forbid an ordinary occurrence: the full breakup, destruction, and dissolution of a marriage.

Cornes’ Concession

That much is relatively clear. And it is important to pause here and emphasize that, up until this point in Matthew 19 (verse 6), all Jesus’ words are consistent with one conclusion: Marriage can, indeed, be dissolved by humans.

On this point Andrew Cornes is admirably clear and honest. Even though he ultimately argues for “the impossibility of true divorce or remarriage,” at this stage in his analysis of Jesus’ conversation with the Pharisees, Cornes pauses to make the following statement:

Jesus has not (yet) said that husband and wife cannot be separated, that this is an impossibility. He has only said that they must not be separated. He has spoken only of the moral obligation not to divorce and stated that it would be a sin against God to divorce one’s partner or to cause the break-up of a marriage. In the next verses, however, he goes considerably further.[3]

(In fact, Cornes wrote this comment right after his discussion of Mark 10:9. Since Mark’s account varies slightly from Matthew’s, Corne’s comment covers not only all Jesus’ statements we’ve discussed so far but also his comments about Moses, which Matthew includes in verses 7 to 8.)

Was Jesus Prohibiting Only the External Separation of Marriage?

Those who don’t think Jesus meant humans can truly separate what God has joined, then, come to that conclusion either based on alternate readings of terms like one flesh or because of what Jesus says later in the passage. For example, here is the assessment offered in Divorce and Remarriage: A Permanence View, a multi-author book that some conservative Anabaptists recommend:

Jesus’ prohibition of divorce in Matthew 19:6 and Mark 10:9 is sometimes thought to refute the above point [that a marriage “union is permanent until death”]. Since He commands us not to separate what God has joined together, it is reasoned that it is possible to separate what God has joined together. After all, why would He prohibit us from doing something that is impossible? But by looking at the matter in its fuller biblical context (as is the intent of this book), we will see that Jesus must have been prohibiting the external separation of marriage. The vows spoken at a wedding can certainly be disregarded, and a marriage certainly can be separated in civil and legal ways, but these external disruptions of marriage do not and cannot destroy the morally binding one-flesh union created by God. Otherwise, no reason would exist for Jesus to call remarriage after divorce “adultery.”[4]

This paragraph is so full that I can’t offer a comprehensive response here. The authors wrote a book to try to prove their argument and it could take a book to respond. That said, I want to make several quick observations.

First, yes, it is theoretically possible that Jesus could have meant don’t legally or physically separate a union that it is impossible to truly separate. It is possible, and it can appear almost certain, if you bring particular assumptions to the text. The four reasons I presented above, however, strongly indicate that Jesus knew his first listeners would not understand him this way. I see no reason to abandon the most natural reading unless forced to do so.

Second, notice how these authors, right at the climax of their argument, described marriage as “the morally binding one-flesh union created by God.” This pile-on of emotion-laden terms is a non-argument obviously intended to help convince the reader. I say “non-argument” because “morally binding” merely shows one should not separate a marriage, not that one cannot. And the only term in that clause that could perhaps indicate that marriage is indissoluble—“one-flesh”—actually does not, as we have seen.

Third, and most important, the one actual argument the authors offered is based on what Jesus will say later in this account, when he calls remarriage after divorce “adultery.” If it is possible to separate a one-flesh union created by God, then how could Jesus call a post-divorce marriage “adultery”? This is a good question. In response, I’ll plant two small seeds now, with plans to develop them in future posts:

(1) Yes, Jesus calls remarriage after (some) divorce “adultery,” but what is the biblical picture of what adultery does to a marriage?

(2) What about the exception Jesus gave to the statement that remarriage is adultery? Would not even one exception show that marriage is not truly indissoluble?[5]

For reasons such as these, I find the arguments that Jesus was merely prohibiting the external separation of marriage unconvincing. Certainly he did forbid that, but I believe he was prohibiting complete separation, too.[6]

Complexities and a Conclusion: “Let Not Man Separate” Implies Marriage is Dissoluble

Before I finish this post, I want to observe that there is inevitable complexity about talking about marriages that have been ended. For example, when Jesus says one who “marries” another “commits adultery,” he affirms that a remarriage is indeed a marriage even as he condemns it (Matt. 19:9, etc.). Similarly, Paul says a divorced Christian wife “should remain unmarried or else be reconciled” to her Christian husband (1 Cor. 7:11). His words show that it is possible in one breath to talk about marriage having ended (“unmarried”) but about obligations still remaining.[7]

Both examples underscore again the necessity of distinguishing between the “could” and “should” of Scripture. It must also be noted that neither Jesus nor Paul apply the above statements to all divorce and remarriage situations; Jesus did not say all divorces and remarriages are adultery, nor did Paul say obligations remain after every kind of divorce.

Given these complexities, I acknowledge I puzzled long and hard over how to express myself in this post. I encourage both “sides” (those arguing for marriage indissolubility and those arguing against) to be kind to each other as we try to discuss a question of some philosophical complexity. Almost certainly, no matter which position we take, we will say some things that appear superficially contradictory (like Jesus and Paul did!). We must be gracious with each other while pushing for greater accuracy and clarity.

This post has uncovered points that will require further consideration. That said, I want to end by underscoring my main point in this post: Everything Jesus has said thus far in his conversation with the Pharisees (Matthew 19:3-6) suggests we should take Jesus’ command in its most natural, comprehensive sense: Humans can indeed dissolve the union that God creates in marriage, but they must not do so.

Will further evidence override this conclusion? In my next posts I plan to continue walking through Matthew 19, looking for more clues to what Jesus believed about marriage permanence.

I invite your prayers for my continued study and writing. Thank you for reading my words here, and feel free to add your insights in the comments below.

If you want to support more writing like this, please leave a gift:

[1] R. T. France, The Gospel of Matthew, New International Commentary on the New Testament (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2007), 718.

[2] John Piper, “Divorce & Remarriage: A Position Paper,” Desiring God Foundation, 7/1/1986, accessed 6/14/2022, https://www.desiringgod.org/articles/divorce-and-remarriage-a-position-paper

[3] Andrew Cornes, Divorce and Remarriage: Biblical Principle and Pastoral Practice (Fearn, Scotland: Christian Focus Publications, 2002), p. 192. I have much respect for Cornes even though ultimately I have come to disagree with him on the point of whether marriage is dissoluble. Cornes’ book includes exceptionally helpful reflections on singleness in the Bible and the church.

[4] Steve Burchett, Jim Chrisman, Jim Elliff, and Daryl Wingerd, Divorce and Remarriage: A Permanence View (Kansas City, MO: Christian Communicators Worldwide, 2009), p. 17.

[5] Yes, I know I haven’t proven this point yet, but I’m tipping my hand to the reading of Jesus’ exception clause that I find most convincing.

[6] It might be worth mentioning in passing that in Mark’s account of Jesus’ discussion with the Pharisees about divorce, they never hear him call divorce and remarriage adultery; only the disciples hear Jesus give this teaching after they question him privately “in the house” (Mk. 10:10-11). This eliminates the possibility, at least according to Mark’s version of events, that the Pharisees would have deduced from Jesus’ adultery statement that marriage was—contrary to all their understandings as Jews—indissoluble.

[7] A helpful chapter on this topic (“Are Divorced People Still Married in God’s Eyes?”) is included in the following wide-ranging, yet accessible, book by Jim Newheiser: Marriage, Divorce, and Remarriage: Critical Questions and Answers (Phillipsburg, NJ: P&R Publishing, 2017), 230ff.