This post continues my series on Jesus, divorce, and remarriage (JDR), where I’m currently walking through Matthew 19. To understand my goals in this series, please see my past posts, especially the first two:

Jesus on Divorce and Remarriage: Introduction (JDR-1)

Hyper-Literalism, Could vs. Should, and a Guiding Question (JDR-2)

“Cleave” Does Not Imply an Unbreakable Bond (JDR-3)

“One Flesh” Does Not Imply an Unbreakable Bond (JDR-4)

“God Has Joined Together” Does Not Imply an Unbreakable Bond (JDR-5)

Genesis 2:24 as God’s Creation Norm for Marriage (JDR-6)

“Let Not Man Separate” Implies a Breakable Bond (JDR-7)

“Moses Allowed You to Divorce” Suggests a Breakable Bond (JDR-8)

Why Did “Hardness of Heart” Cause God to Allow Divorce? (JDR-9)

“Hardness of Heart” and Jesus’ Audience, Then and Now (JDR-10)

“From the Beginning It Was Not So”—And Never Has Been (JDR-11)

Summary of this post: I consider the relationship between (1) God’s creation standard for marriage, (2) what the law of Moses said about divorce, and (3) Jesus’ divorce teachings. Contrary to the assumptions of the Pharisees, the giving of the law did not make God’s creation standard irrelevant. Similarly, I argue, Jesus intended to clarify rather than overturn the law of Moses. His divorce teachings are consistent with those of Malachi, an earlier Jewish prophet who likewise affirmed the law of Moses. Thus, just as the creation account offers Christians today an essential vision of God’s ideal for marriage, so the OT divorce laws can help us understand his will for responding to hard-hearted covenant breakers.

Creation and the Law: Consecutive Standards, or Concurrent?

In my last post I explained why “in the beginning it was not so” is a bad translation of Jesus’ words in Matthew 19:8, which are better translated as “from the beginning it has not been so.” I’ll pick up where we left off by once again quoting Luck’s comments on the same clause:

Jesus is not trying to distinguish between a dispensation up to Moses, followed by a hiatus, in turn terminated by Jesus’ present teaching, but rather a continuing divine attitude that runs clear from the beginning of creation up to the point of the Lord’s speech—right through the time of Moses and the exercise of the Law![1]

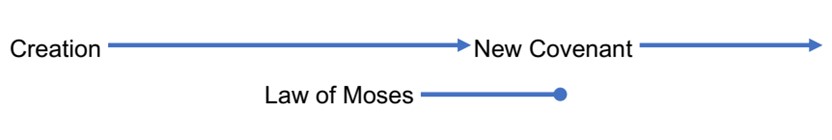

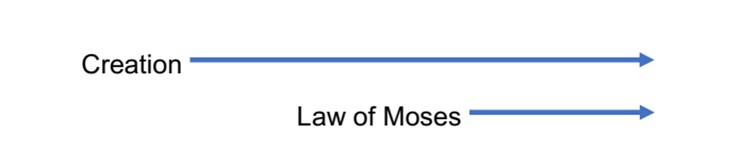

We can display Luck’s argument visually by contrasting several timelines.

The Pharisees based their divorce teaching entirely on the legal portions of the law of Moses. If they thought about God’s creation purpose for marriage at all, they apparently assumed it had been superseded by Moses’ allowance of divorce, as this consecutive timeline suggests:

In this conception of things, the Jews were off the hook if they failed to live up to God’s creation purpose for marriage permanence, for its relevance had ended with the giving of the law of Moses.[2]

Jesus sharply rebuked this attitude, insisting instead that God’s creation purpose remained unchanged, despite God’s allowance of divorce in the law of Moses. In Jesus’ perspective, God’s primary will and his secondary will ran concurrently, so that Jesus could still call his hearers to God’s higher standard, despite Moses’ divorce allowance: We should not, however, draw too sharp a division between creation and law. In our English translations of the OT, the word law is traditionally used to translate the Hebrew word torah (tôrâ). In Hebrew thought, however, torah is often understood more broadly and could be better translated as instruction or teaching. When Jews spoke of “the Torah” they meant everything found in the books of Moses, including not only commands but also narrative portions—including the creation account. Consider Meier’s warning:

We should not, however, draw too sharp a division between creation and law. In our English translations of the OT, the word law is traditionally used to translate the Hebrew word torah (tôrâ). In Hebrew thought, however, torah is often understood more broadly and could be better translated as instruction or teaching. When Jews spoke of “the Torah” they meant everything found in the books of Moses, including not only commands but also narrative portions—including the creation account. Consider Meier’s warning:

It is unfortunate that some commentators (betraying a theological concern with Law within a particular Christian context) speak in too sweeping a fashion of… Jesus opposing creation to Law. In reality, the creation narrative of Genesis is the beginning of the whole Torah, the whole Law, of Moses.[3]

Perhaps, ironically, we are guilty of a similar interpretive stumble as the Pharisees if we imagine that creation and law should not be taken together as parallel witnesses of God’s will, a complete Torah (teaching) that includes both his original purposes and his concessions.

The Law and Jesus: Consecutive Standards, or Concurrent?

The second timeline above clarifies that God’s creation purpose was not terminated when the law of Moses was given. The timeline leaves another question unanswered, however: Did Jesus mean to revoke God’s secondary will as given in the law of Moses? Was he eliminating all allowance for divorce when he reminded people of God’s original creation design for marriage? Was Jesus saying “it’s God’s primary will or nothing” now that his kingdom was at hand?

Some Bible teachers and scholars seem to think so. Consider again, for example, these words from Coblentz:

Under the Old Covenant God permitted [divorce] in anticipation of the New Testament era in which He would require a higher standard of righteousness… Under the New Covenant, hardhearted husbands and wives can be given new hearts by the transforming power of the Spirit. Jesus the heart-changer has come, and God’s standards for marriage can be restored to His intention “from the beginning.”[4]

The evangelical commentator Hagner expressed a similar view even more forcefully:

The Mosaic legislation in Deut 24:1–4 was… not normative but only secondary and temporary, an allowance dependent on the sinfulness of the people… The new era of the present kingdom of God involves a return to the idealism of the pre-fall Genesis narrative. The call of the kingdom is a call to the ethics of the perfect will of God (cf. the Sermon on the Mount), one that makes no provision for, or concession to, the weakness of the flesh.[5]

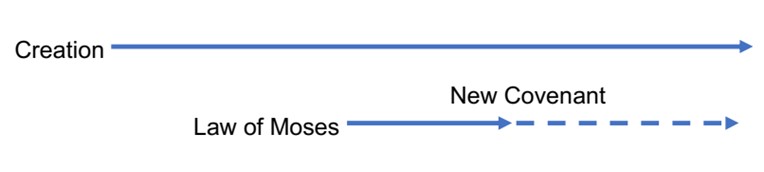

In timeline form, this view looks like this:

According to this view, the coming of the law did not overturn God’s creation standard about divorce. The new covenant, however, did overturn what the law of Moses taught about divorce.

Did Jesus Overturn the Law and Introduce New Divorce Teaching?

There is much that is attractive about this view, and it is at least partly right. The full NT witness makes it clear that Jesus did inaugurate a new covenant and that new covenant believers are no longer under the law of Moses in the same way that OT saints were.[6] It is also true that God’s Spirit gives believers new hearts and can empower them to honor God’s original creation design for marriage. That standard should certainly be the goal of every married Christian.

None of this, however, proves that Jesus was intentionally overturning the law of Moses when he gave his teachings on divorce. Nor does it prove that what Moses law taught about divorce no longer has any relevance for new covenant believers. The fact that the law of Moses could be given while God’s creation standard remained relevant should make us ask: Could the law of Moses remain relevant in some way while Jesus calls us back to God’s creation standard?

The answer is surely Yes, according to the literary and historical contexts of Jesus’ divorce teachings. In both Matthew 5 and Luke 16, Jesus introduced his teaching on divorce by emphasizing the abiding relevance of the law.[7] Similarly, in Jesus’ divorce debate with the Pharisees, they “tested” him using the standard of the law: “Is it lawful to divorce one’s wife…?” (Matt. 19:3). If Jesus had contradicted or overturned the law, his enemies would have pounced.[8]

But they don’t pounce, because “Jesus avoids nullifying Deuteronomy. Instead, he affirms the validity of both Genesis and Deuteronomy as (respectively) ‘creation prototype and wilderness proviso.’”[9] In answer to the Pharisees’ question, “Is it lawful?” Jesus essentially answers, “Yes—but you’re avoiding another question that’s even more important: ‘Is it consistent with God’s original and highest will?’”[10] With this answer, he avoids their trap, refusing to either approve their selfish divorces or contradict the law of Moses.

But what about the new covenant? Didn’t it overturn the law of Moses?

Given what one hears from some Bible teachers,[11] it can come as a surprise to notice that Jesus never appealed to the new covenant when teaching on divorce. He only pointed backwards to creation, never forward to the coming of the Spirit. Despite brief contextual references to the present inbreaking of the kingdom of heaven,[12] in his divorce teaching “Jesus [did] not appeal to the new eschatological situation brought about by the arrival of the kingdom of God… but rather to God’s purposes in creation.”[13]

In sum, Jesus presented his divorce teaching as a clarification of existing truth, not as something new. He seemed to think that what he was teaching about divorce was what Jewish leaders should have been teaching all along, before he ever arrived on the scene.

Jesus and Malachi: Two Jewish Prophets Address Divorce

Indeed, Malachi— the last OT prophet to teach on divorce—did just that. I would argue that Jesus said nothing in his Matthew 19 divorce teaching that was different in essence than what the prophet Malachi had already said over 400 years earlier. Put differently, everything Jesus said about divorce and remarriage in the Matthew 19 account either had already been taught by Malachi or fits perfectly with what he wrote.

Note the similarities:

- A central concern for both Malachi and Jesus was men who practiced “aversion divorce”—divorcing wives without valid cause, often because they wanted new ones.

- Malachi began his discourse on divorce by asking “Has not one God created us?”, presenting this as an argument against being “faithless to one another” (Mal. 2:10; cf. 2:15). Jesus similarly began with creation: “Have you not read that he who created them from the beginning made them male and female?” (Matt. 19:4; cf. 19:5, 8), using that as a basis for preserving marriages.

- Malachi emphasized that marriage was a “covenant” (Mal. 2:14). Jesus likewise emphasized the covenantal expressions “hold fast” and “one flesh” (Matt. 19:5-6).

- Both described aversion divorce as being an affront against God himself, who is described as the one who unites a husband and a wife (Mal. 2:14-15; Matt. 19:6).

- Both honored wives, recognizing their dignity and legal rights more than was common in Jewish culture. For example, both warned that aversion divorce was a crime against one’s wife (Mal. 2:14; Matt. 19:9; cf. Mark 10:11, “against her”).

- Finally, the central term in Malachi’s critique of divorce was “faithless” (or “unfaithfulness,” NIV; Mal. 2:10, 11, 14, 15, 16) which foreshadowed Jesus’ more pointed punchline that he who divorces and remarries “commits adultery” (Matt. 19:9; cf. Matt. 5:32; Mark 10:11-12; Luke 16:18).

Stuart says the following about the divorces in Malachi’s day:

Their aversion-divorce decrees were pure “unfaithfulness.” This divorce that they were practicing was just as much “unfaithfulness” as if they were committing adultery.

And did not Jesus say just this about aversion divorce? His words are entirely consistent with the view of marriage enunciated in Malachi’s third disputation: “Whoever divorces his wife, except for unchastity, and marries another commits adultery” (Matt. 19:9).[14]

Given these similarities, Carson suggests that “Jesus aligns himself with the prophet Malachi”[15] and some commentators have even suggested that Jesus, in his debate with the Pharisees, was using Malachi to interpret Deuteronomy 24.[16] Whether or not Jesus was indeed thinking of Malachi as he taught on divorce, the similarities between their prophetic warnings are evident.[17]

This raises important questions. When Malachi rebuked aversion divorce so sharply, was he overturning the divorce allowance found within the law of Moses? This hardly seems feasible, since OT prophets functioned as covenant enforcers, holding Israel accountable to keep God’s law from the heart.

What, then, about Jesus? If Malachi was not overturning Moses’ divorce allowance,[18] and if Jesus’ words “are entirely consistent with the view of marriage enunciated in” Malachi, then what basis do we have to conclude that Jesus intended to overturn Moses’ divorce allowance? Isn’t it more consistent to see him, like the latter prophets, urging Israel to keep “the weightier matters of the law: justice and mercy and faithfulness… without neglecting” the legal details they so often emphasized or abused (Matt. 23:23)?

Does the Law of Moses Speak to Christians Today?

But what about the Christian today, who is a member of Jesus’ new covenant community in a way that Jesus’ original audience of Pharisees never was? Does the law of Moses, with its divorce allowances and commands, have any relevance for us?

A good approach, it seems to me, is to acknowledge both continuity and discontinuity regarding the law of Moses for the Christian today. On the one hand, we are no longer members of the Mosaic covenant and therefore not directly under its law. On the other hand, the law of Moses still reveals eternal realities about the heart of God and about his concern for justice, mercy, and faithfulness in marriage. Just as we affirm many things the law of Moses says about sexuality in general[19] while relaxing or adapting others,[20] so the Mosaic divorce permissions and commands still have some relevance for us today.

All parts of the Torah remain “profitable” for the Christian today (2 Tim. 3:16). Just as the creation account offers an image of God’s ideal for marriage, so the OT divorce laws can help us understand his will for responding to hard-hearted covenant breakers. Hard hearts, after all, exist as much today as they did in the days of Moses and Jesus.

No, we should not use OT laws to override clear NT teachings. But neither should we assume a total break with all that the OT law teaches about divorce. Jesus didn’t—and neither, for that matter, did Paul (see Rom. 7:2).

Expressed as a timeline, the view I am proposing could look like this, with a dashed line showing a that the law of Moses still has indirect relevance for the Christian today:

Some of us aren’t as comfortable with a dashed line as with a solid line or a period. Black-and-white law can be more convenient than ambiguity. The view I’m proposing requires us to seek God’s heart and not merely his rules, important as they are.

Conclusion: Final Quotes to Ponder

I want to wrap up this long post with a couple long quotes from authors who share my reading of Matthew 19:8. First, here again is our text:

“Because of your hardness of heart Moses allowed you to divorce your wives, but from the beginning it was not so [has not been so].”

Here is Frederick Dale Bruner’s commentary:

This text has been understood in two main ways. (1) Jesus opposes Moses, cancels Deuteronomy’s permission, and so contrasts divorce with God’s will “from the very beginning.” Deut 24 is not God’s will for Jesus at all; it is only Moses’ concession. Or (2) Jesus demotes Moses’ concession, subordinating Deuteronomy’s “Second Law” to Genesis’s “First Law.” Yet, this argument concedes, Deut 24 is God’s permitted, “second” will for some persons.

I understand the text in the second sense because Jesus does not say, antithetically, “You have heard of old, ‘Because of your hard-heartedness Moses permitted you to divorce your wives,’ but I say to you, this must no longer be the case.” Jesus does not substitute; he subordinates. He does not replace Moses’ teaching with his own but subjects Deuteronomy to Genesis. But Deuteronomy remains. Deuteronomy is the subordinated, concessioned, qualified, but still valid will of God… Matthew’s Jesus takes both laws, places them in a clear first and second place, and then seeks in every way possible to move his disciples to seek God’s first will.

…Jesus read Scripture discriminately, even hierarchically, placing some texts over others in authority. Scripture was not flat to Jesus; it had peaks and valleys, higher truth and subordinate truth…

Genesis (the “Beginning” Book) gives us God’s pristine will on marriage; Deuteronomy gives us God’s permissive will for failed marriage; Genesis is Primary Will, Deuteronomy is Secondary Will. For those to whom Jesus is Lord, these two teachings—of Genesis and of Deuteronomy—will not be seen as two equal or even close options, but as the Lord’s passionately-to-be-sought highest will and as his only finally, penitently-to-be-accepted last resort.[21]

Barbara Roberts views the Mosaic witness more holistically than Bruner, without setting creation against law code. She also adds crucial words affirming innocent spouses. Yet she agrees with Bruner’s main point—and mine—that Jesus did not replace Moses’ teaching with his own:

It is not the case that Jesus simply abrogated the Mosaic divorce law and instituted a new, more stringent divorce rule for kingdom living. The Mosaic Law had always set forth the divine intention that marriage was a lifelong committed relationship. It had sought to protect a vulnerable, innocent spouse from a callous or unfaithful spouse, and had allowed the use of disciplinary divorce. It had sought to deter people from treacherous, cavalier and impulsive divorce and remarriage.

Jesus did not change any of this; he simply called for a full and proper adherence to God’s standards for marriage. He condemned the legalistic approaches of his own day, which had legitimized treacherous divorce. And he declared that treacherous divorce with ensuing marriage is equivalent to adultery and a breach of the seventh commandment. If this appeared to be changing the standard, it was only because the Jews had so poorly adhered to the standard.[22]

I realize some readers will remain unconvinced. For some, anything short of an absolute enforcement of God’s creation standard against divorce feels like an unjustifiable compromise, unsuited to the new covenant and the kingdom of God. For such readers, I’ll share one more quote. It is pregnant. I invite you to ponder this:

It is true that from the beginning men did not divorce their wives… We may note in passing that, from the beginning, neither was there a separation from bed and board.[23]

If you made it this far, thanks much for reading! Up next is Matthew 19:9, which is Jesus’ climatic statement on divorce in this whole account. I have lots of thoughts I hope to share on this verse but don’t have any blog posts drafted yet, so you may have to wait a couple months for my next post. Meanwhile, feel free to share your thoughts in the comments below. Thanks again!

If you want to support more writing like this, please leave a gift:

[1] William F. Luck, Divorce and Re-Marriage: Recovering the Biblical View, 2nd ed. (Richardson, TX: Biblical Studies Press, 2008), 157-58. Available online: https://bible.org/series/divorce-and-re-marriage-recovering-biblical-view.

[2] Kauffman’s use of the phrase “in the beginning” suggests a similar interpretation: “Moses permitted man to give a writing of divorcement, but it was not so in the beginning, neither is it under the Gospel.” Daniel Kauffman, Bible Doctrine, (Scottsdale, PA: Mennonite Publishing House, 1914), 452. Available online: https://books.google.com/books/about/Bible_Doctrine.html?id=NmkCQ0br9OUC

[3] John P. Meier, A Marginal Jew: Rethinking the Historical Jesus, Vol. IV, Law and Love (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2009), 177, n. 143.

[4] John Coblentz, What the Bible Says About Marriage, Divorce, and Remarriage (Harrisonburg, VA: Christian Light Publications, 1992), 21-23. I want to also take this opportunity to underscore that, having met John Coblentz personally and heard him speak, I deeply respect him.

[5] Donald A. Hagner, Matthew 14–28, Word Biblical Commentary, Vol. 33B (Dallas, TX: Word Books, 1995), 548–549. Blomberg expressed a similar view: “Jesus does not challenge their logic, only the permanence of the Mosaic law. God’s provisions for divorce were temporary, based on the calloused rebellion of fallen humanity against God. He did not originally create people to divorce each other, and he therefore does not intend for those whom he re-creates—the community of Jesus’ followers—to practice divorce. As in the Sermon on the Mount, Jesus proclaims a higher standard of righteousness for his followers than the law of Moses. This distinction suggests that we must be more lenient with non-Christians who divorce but also that we may not include ‘hard-heartedness’ as a legitimate excuse for Christians divorcing.” Craig L. Blomberg, Matthew, New American Commentary (Nashville, TN: B&H Publishing, 1992), 291.

[6] See Rom. 10:4; Gal. 3:17-26; Eph. 2:15; Col. 2:16-17; Heb. 7:12; etc.

[7] See Matt. 5:17-20 and Luke 16:16-17. The latter passage presents two balancing realities. On the one hand, “the Law and the Prophets” are either superseded or fulfilled by “the good news of the kingdom of God.” On the other hand, “it is easier for heaven and earth to pass away than for one dot of the Law to become void,” and one way to understand the sequence of Luke’s account is that Jesus presented his teaching on divorce as evidence of the latter reality—as an example of a teaching of the Law that the Pharisees were failing to observe, a teaching that remained relevant with the coming of the kingdom.

[8] See Matt. 12:2, 10; 22:17; cf. Acts 6:11,13; 21:28; 25:8.

[9] Jeannine K. Brown and Kyle Roberts, Matthew, Two Horizons New Testament Commentary (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2018), 259, quoting F. Scott Spencer, “Scripture, Hermeneutics, and Matthew’s Jesus,” Interpretation: A Journal of Bible and Theology, Vol. 64, No. 4 (2010), 377.

[10] I am disagreeing here with Kuruvilla’s commentary on Mark’s account: “Jesus is questioned about whether or not divorce is lawful at all… In response, Jesus sends his examiners back to Genesis to first understand the nature of marriage. To address divorce, Jesus appeals to the one-flesh union as the basis of comprehending marriage. On this basis, He declares that man should not separate what God has joined together. The answer to the Pharisees’ question about divorce being lawful is evidently ‘no.’ The reader is urged to carefully re-examine the above passage [Mk. 10:2-12] to fully appreciate this point: Jesus was undercutting the Mosaic law’s tolerance of divorce. What the Mosaic law merely restricted, Jesus now forbids.” Finny Kuruvilla, “Until Death Do Us Part: Is Remarriage Biblically Sanctioned After Divorce?” (essay), (Anchor Cross Publishing, July 13, 2014), 6, https://static1.squarespace.com/static/570e3c2f8259b563851efcf8/t/5911288c4402435d4e08c196/1494296716383/essay_remarriage.pdf

[11] See Coblentz and Hagner above. See also Daniel Kauffman’s reference to divorce not being permitted “under the Gospel” in a quote in my last post. Edwards’s suggestion is also questionable: “Mark 10:1-12 is a blueprint for an entirely new norm of marriage.” James R. Edwards, The Gospel According to Mark (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2002), 305.

[12] Mentioned in Matthew’s account (Matt. 19:12) but not by Mark. In both the Sermon on the Mount and near Luke’s record of Jesus’ divorce teaching, though the kingdom of heaven/God is mentioned, Jesus underscores the enduring relevance of the law as a moral standard (cf. Matt. 5:17-20; Lk. 16:16-17).

[13] Robert H. Stein, Mark, Baker Exegetical Commentary on the New Testament (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2008), 456.

[14] Douglas Stuart, “Malachi,” The Minor Prophets: An Exegetical and Expository Commentary, Vol. 3, ed. Thomas Edward McComiskey (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Books, 1998), 1338. Stuart later says the following about Malachi’s divorce teaching: “Because of its reinforcement in the teaching of Christ, it cannot be dismissed as no longer binding on New Covenant believers” (1344).

[15] “Jesus aligns himself with the prophet Malachi who quotes Yahweh as saying, ‘I hate divorce’ (2:16), and also refers to creation (2:14–15)” (Carson, D. A.. Matthew (The Expositor’s Bible Commentary) . Zondervan. Kindle Edition.).

[16] “[Malachi] 2.10-16… begins with a reference to God’s creation of humanity (v. 10: ‘Did not one God create us?’) and continues a few verses later with an apparent allusion to Gen. 2.24: ‘Did he not make one?’… It has therefore been argued that the rejection of divorce is based upon a reading of the creation story… This sets Malachi’s criticism of divorce squarely beside the same two verses quoted in the gospels… In view of this, we find attractive Sigal’s suggestion… that ‘Jesus exegetes Deut. 24.1 in the light of Malakhi.’” See W. D. Davies and Dale C. Allison, Jr., A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the Gospel According to Matthew, Vol. III (London: T&T Clark, 2004), 12. The quote from Sigal can be found in Phillip Sigal, The Halakhah of Jesus of Nazareth According to the Gospel of Matthew, Studies in Biblical Literature, No. 18 (Atlanta, GA: Society of Biblical Literature, 2007 [orig. pub. 1986]), 116: “Jesus stands with Malachi and in line with Malachi’s admonition to ‘remember the Torah of Moses.’ Jesus exegetes Deut. 24:1 in the light of Malachi… Jesus is not thereby annulling Deut. 24:1. He is only exegeting it.”

[17] There are differences, too, though arguably not contradictory ones: Malachi warns against marrying pagan wives, a problem Jesus never mentions. And, unlike Malachi, Jesus mentions “divorce certificates” (alluding to Deut. 24:1).

[18] Stuart (“Malachi,” 1343) says, “Moses and Malachi come at the issue of divorce from different angles. Moses allows it under certain conditions. Malachi condemns it except under certain conditions. But inasmuch as those conditions appear to be identical, employing even the same essential vocabulary in definition of the actions involved, their respective doctrines are compatible.”

[19] For example, adultery, incest, and rape are still wrong.

[20] For example, the death penalty is no longer prescribed for adultery, sex during menstruation is reduced to a question of personal dignity, and polygamy is discouraged.

[21] Frederick Dale Bruner, Mathew: A Commentary; Volume 2: The Churchbook: Matthew 13-28 , rev. and exp. ed. (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2004), 260-61. Davies and Allison, quoting Cranfield, present a view which is virtually identical to Bruner’s. See W. D. Davies and Dale C. Allison, Jr., A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the Gospel according to Saint Matthew, Vol. III (London: T&T Clark, 1997), 14. Google preview: https://www.google.com/books/edition/Matthew/ZXIV2WOTVvMC?hl=en&gbpv=1&bsq=%22from%20the%20beginning%22

[22] Barbara Roberts, Not Under Bondage: Biblical Divorce for Abuse, Adultery and Desertion (Ballarat, Victoria, Australia: Maschil Press, 2008), 88.

[23] Guy Duty, Divorce and Remarriage: A Christian View (Minneapolis, MN: Bethany House Publishers, 1983), 68-69. Unfortunately, Duty reads “from the beginning” as if it meant “in the beginning.” Yet, his point remains valid: Separation from bed and board (“moving out” without divorcing) is no more a part of God’s original design or perfect will than divorce is. Yet, who among us would argue it should never be done? Therefore, merely noting that something was not part of God’s original design does not prove it is always wrong. We do not live in Eden, and requiring others to live as if they do can cause great harm. It is clear Jesus was urging us to follow the creation ideal and rebuking those who are to blame for breaking it. This does not mean, however, that he was ruling out making accommodations for situations where others have already broken that creation ideal.