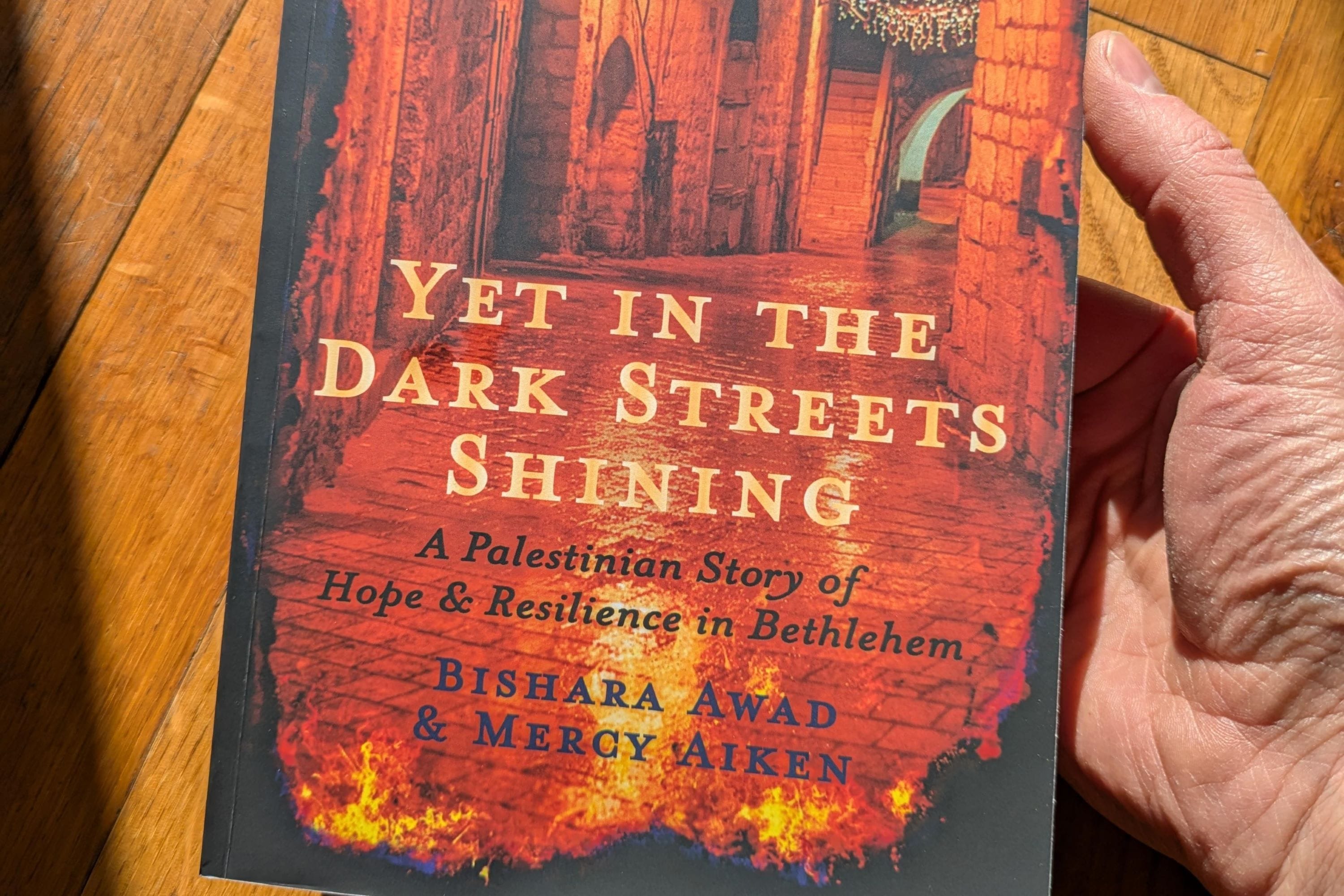

One gift I received this Christmas was a book on my wish list: Yet in the Dark Streets Shining: A Palestinian Story of Hope and Resilience in Bethlehem.

The book presents snapshots from the childhood and ministry of Bishara Awad, a remarkable Palestinian Christian who founded Bethlehem Bible College (BBC). It was cowritten in 2021 by Awad and Mercy Aiken, an American who came to BBC in 2015 as a volunteer.

This is a book that more North American Christians should read. It gives a perspective that is often overlooked by American evangelicals, including many Anabaptists: the testimony of our Palestinian brothers and sisters who have lived for centuries in the Holy Land. Although Yet in the Dark tells this story only up to 2002, it is more relevant than ever, given that the "hopes and fears of all the years" of Palestinian Christian history are being tested right now perhaps more than ever. (See this article about another Palestinian pastor who is the current academic dean of BBC and also director of Christ at the Checkpoint, a conference challenging evangelicals to become kingdom Christians and help resolve the conflict in Israel and Palestine.)

Yet in the Dark moved me for many reasons.

One unforgettable character is Awad's mother, who is an astounding example of faith and forgiveness. In spite of losing her home, husband, and almost her own life to the violence of Jewish settlers, and therefore needing to scatter her children to multiple schools and orphanages to keep them barely alive, she never stopped praying to a miracle-working God and never stopped forgiving her enemies. "We need to pray for the Jews. They've suffered terribly in Europe" (p. 13). "Lord, we forgive whoever fired that bullet this morning" (p. 20, after burying her husband in the only place available, their own backyard).

I was fascinated to learn that "almost all" Palestinian Christians at the time of the birth of the modern nation-state of Israel "held to the Lord's teaching on this subject," believing that "Jesus taught us to lay down our swords and love our enemies. Period" (p. 14). Later in the book, a youth who is wrongfully imprisoned and horrifically tortured by the Israelis emerges with an even deeper faith and love: "I want to understand the pain that drives the Israelis to do what they do to us" (p. 141).

Another powerful picture displayed by Yet in the Dark is the composite image of Arab peaceful coexistence before and after the birth of the Jewish nation. Despite differences and limits on their interactions, Muslim and Christian Palestinian Arabs generally cared for each other, bound by a shared history of living under centuries of occupation. Kind Muslims intervened sacrificially at crucial times to save the Awad family. More recently, this mutual peace has been tested, due in part to the rise of fundamentalist Islamic groups that were born in resistance to the Israeli occupation of Arab lands.

A similar but deeper unity grew between Christian denominations in Palestine, as they learned to pool their increasingly limited resources in the common goal of providing Christian education and leadership for their people. Here is Awad's perspective:

Some who converted under the new Protestant missionaries felt it necessary to disavow their previous denomination. Mother never took that approach. She taught us to appreciate the good from all denominations, including the Greek Orthodox Church that was her family heritage and the Maronite church that was our father's heritage. Mother's position always made sense to me. I considered myself a mixture of all who helped to build and shape my faith through the years, including the Greek Orthodox, Pentecostals, Methodists, Mennonites, and others. (p. 99)

Yes, Mennonites.

That was a surprise for me as I read this book—how much Mennonites directly shaped Awad's life and ministry. Some examples:

- In 1961 Mennonites founded a school near Bethlehem for disadvantaged Palestinian boys. Bishara Awad's brother Mubarak worked there and he "challenged the Mennonites to introduce materials into the boy's curriculum about their history of pacifism" (81). In 1972 the Mennonite Central Committee (MCC) asked Bishara to take over as principal, with the goal of establishing local leadership and financial independence.

- In one incident, a formidable "papa bear" visitor from the MCC persisted boldly with a Jewish commander until he agreed to release three Palestinian students who had been arrested. "They are under the care of the Mennonite church. We demand their release" (p. 92).

- In 1981 (after the founding of BBC), the Mennonite Church paid the way for Awad and his family to come to Fresno, California for one and a half years of training at the Mennonite Brethren Biblical Seminary there.

- This training broadened Awad's vision for BBC: "Deeply appreciative of the nonviolent stance of the Mennonite Church, I also wanted to see serious theologians emerge from the Palestinian church with the same clear message of Christian pacifism... The leaders that I envisioned would not advocate for violent overthrow of the systems of this world, but rather seek to undermine them with goodness and grace by putting the gospel into action" (pp. 107-108).

This leads me, frankly, to one of my most conflicted responses to this book.

According to this book, Bishara Awad's brother Mubarak "played a leading role in initiating the intifada," the Palestinian movement aimed at "shaking off" (the meaning of intifada) the degradation of the Jewish occupation (p. 125). This intifada began as a nonviolent movement, for "non-violence was an idea he [Mubarak] wholeheartedly embraced during his turbulent years in America where he observed the work of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr." (p. 81).

As I read this part of Yet in the Dark, I felt all the same ambivalence I have felt as I've read the writings and history of King and his resistance movement—an ambivalence I've also felt about some expressions of the Mennonite pacifism that also shaped Mubarak. (Indeed, Mennonites and King also shaped each other; see here.)

Mubarak posted signs like "How to get your rights without firing a single bullet." He "had no qualms about breaking Israeli law" and refused to pay taxes (p. 126-27), which is directly contrary to what Paul taught under Roman occupation (Rom. 13:7). After one Palestinian community, "inspired by the American Revolution," adopted the slogan of "no taxation without representation" in their "nonviolent" protest, the Israelis put the entire town under house arrest for forty days, cut telephone lines, and confiscated property (pp. 142-43).

Does this approach fully mirror the way of Jesus? Or is it still too focused on rights and resistance and not enough on cross-bearing enemy love? Does Jesus advocate hurting others (damaging possessions, preventing income) as long as that hurting doesn't result in bodily harm? Or does such an insistence on securing rights inevitably produce a mindset where nonviolence becomes unsustainable, growing into the famous stone-throwing of the intifada and worse forms of violent resistance?

Bishara Awad says "I would never be as politically minded as Mubarak, but I supported my brother's activism... Even so, I saw our issues more through a theological lens than a political one... More than anything, I wanted us to have a Christ-like response to everyone, even the Israelis" (p. 129). I don't want to criticize these Palestinian Christians too harshly; again and again they showed incredible restraint and generous enemy love, more than I often give. That said, I do think that even non-violent resistors can be invited to follow Christ's path more fully.

(I'm sure I'd also discover other points of disagreement with Awad and other Palestinian Christians--just as I have strong disagreements with some of the persons whose endorsements appear on this book's cover--but few such disagreements appeared as I read.)

If I'm ambivalent about the nonviolent resistance of some Palestinian Christians, I am in utter disagreement with the Christian Zionism described in this book.

I could give many examples, but here is perhaps the worst. Sit with your Palestinian brother Awad in this gathering of Christians:

"We need to pray for Israel in her time of struggle," said my friend as she ministered from the stage. A murmur of amens rippled across the room. I was ready to pray for Israel; it was part of my practice. What I was not prepared for was what came out of her mouth next.

"The Lord is showing me that Israel needs more than our prayers. We need to put some actions to our prayers. Tonight, I believe the Lord is calling us to raise the money to buy a tank for the Israeli Defense Forces. Who is ready to give sacrificially to this cause? ...Remember, world redemption depends on Jews being back in the land that God promised to them! Who will pledge ten thousand dollars? Who will pledge twenty thousand dollars?"

...Around the room, millionaires were raising their hands and standing up as they committed to give to the project.

...I snapped back to attention, to a scene that was as equally baffling as painful. People were laying hands on one another, praying. Some had their arms lifted in a posture of worship, tears streaming down their cheeks.

"Hallelujah, we have a pledge for twenty thousand dollars! Give the Lord a praise offering!" Around the room people were applauding and praising the Lord. The musicians were playing softly in the background to minor chords of a Jewish-style worship song.

Do any of these people understand that this tank may be used to kill their fellow Christians and other innocent people? I wondered. Pain shot through my heart as I considered that even if they knew, it probably would not matter. They were more enamored with what they considered to be the fulfillment of biblical prophecy than with the fate of Palestinians, even if the Palestinians were their own brothers and sisters in Christ.

I felt very alone. (pp. 145-46)

Yet in the Dark is not a theology book, but it does include some brief dialogue scenes where Awad shares a faithful, new covenant way of identifying the children of Abraham and understanding the biblical promises of the land they will inherit.

One of the most moving passages of Yet in the Dark is the scene where Awad finds healing for the anger that remained in his own broken heart.

Some of that anger was directed at Israelis. Some of the brokenness was inflicted by fellow Christians. "Why is it that so many of my fellow Christians are indifferent to our oppression?" he asked the Lord (p. 93). As he prayed, he was given a picture:

In my mind, I saw an image of the Holy Land as a beautiful silver chalice filled with wine, over which the nations had fought. I saw the gleam of greed in the eyes of those who possessed it momentarily, only to watch it slip through their fingers and into the hands of another.

The people themselves, those who lived in the land, were almost irrelevant. From century to century, from empire to empire, who cared about the people? No, it was the ideals, the theology, the worldview, the sentiment that the land represented that each group wanted. Each would defend their idea of nationhood and God at the expense of their fellow human beings made in God's image. To possess the cup, they would sacrifice its contents.

I saw a hand tilting the cup and pouring the wine to the ground, like blood. It was the blood of generations...

And then another image came: Jesus, lifted high on the cross, his blood rolling down his naked body to the Jerusalem soil where it pooled and slowly seeped into the earth. There he was, the chalice itself, simultaneously pouring himself out as a drink offering, while also drinking the bitter cup down to its dregs...

"I forgive, Lord. I forgive... Have mercy on me. Have mercy on us all." (pp. 93-94)

Many more characters and scenes appear in Yet in the Dark—including Horatio Spafford (author of "It Is Well with My Soul"), Winston Churchill (briefly), and (frequently and significantly) Brother Andrew, famous from his book God's Smuggler but also a powerful example of sharing the gospel of Christ's even to the leaders of Hamas.

"Whoever does not love, does not know God, for God is love" (1 John 4:8).

That was the message that Awad and Brother Andrew brought to the leaders of Hamas, and ultimately it is the central message of Yet in the Dark.

It is a hard message. As Awad writes, "If you really love God, prove it by how you treat others, or else be quiet about how spiritual you are" (p. 159).

"Others" includes our enemies, whether Jewish, Palestinian, or people closer to home. "Others" certainly also includes our Palestinian brothers and sisters in Christ.

Are we listening? Do we really love God?

This book left me with deep sadness. Sadness that violence in the Holy Land has only gotten horrifically worse since this book was written. Sadness that so many Christians still show such callous lack of compassion for the suffering of the innocent there.

But this book also left me with hope. If forgiveness and enemy love can flourish in such dry soil... why not anywhere? Yes, this world is often very dark, but "the light shines in the darkness, and the darkness has not overcome it" (John 1:5).

Hallelujah!

If you want to support more writing like this, please leave a gift: