This is part four of a series called “Wanted: Weak Christians.” Here are the other posts:

Wanted: Weak Christians (1 of 5) — Introduction

Wanted: Weak Christians (2 of 5) — Who Are They?

Wanted: Weak Christians (3 of 5) — How Are They Indispensable?

Wanted: Weak Christians (4 of 5) — Advice to the Strong

Wanted: Weak Christians (5 of 5) — The Power of the Powerless

What if your weakness is God’s gift to Christ’s church?

I asked this question at the end of my last post, and I plan to return to it. But first, in this post, I want to (1) summarize this blog series so far, and (2) give some advice to “strong” Christians.

SUMMARY

This blog series is my attempt to encourage discussion of Paul’s teaching about “the parts of the body that seem to be weaker” (1 Cor. 12:22). Here, without adornment, are the main ideas we’ve covered:

- Discussions about the body of Christ usually conjure images of spiritual gifts and individual strengths. But when God “composed the body,” he also intentionally wove into its fabric members who “seem to be weaker,” people whom “we think less honorable” or even “unpresentable.” Valuing only strengths will lead to bad fruit.

- In the analogy of the body, the “weaker” members are the hands and feet, but especially the “necessary” or “private parts,” which we honor by covering with clothing.

- In Christ’s body, the “weaker” Christians are those who tend to be considered weak or embarrassing because of some perceived lack, such as in social status, psychological disposition, aptitude, confidence, spiritual gifting, or knowledge. Often they are perceived as being less “spiritual” in some way. The symptom that is perceived as weakness often truly exists. But more importantly, it exists as “weakness” in the eye of the beholder—in the eyes of other Christians who often feel themselves “strong” by comparison.

- “Weaker” Christians are “indispensable” to the rest of Christ’s body. God gives them gifts that are essential. Further, God uses them to unify the church, as other members share in their suffering and extend them honor. Mutual suffering, even mutual embarrassment, stimulates mutual care, which binds the body together in unity.

- God designed our physical bodies so that our brains, eyes, and hands instinctively work together to honor our crucial reproductive organs with appropriate clothing. In the same way, God designed Christ’s body so that its Spirit-filled members work together to give honor to fellow Christians who appear weaker, knowing they are valued by God and essential to the church. In this way, God gives “greater honor to the part that lacked it.”

God’s composition is not something you or I would have dreamed up. But what if what your world most needs is someone with needs? What if your weakness is God’s gift to Christ’s church?

ADVICE TO THE “STRONG”

On the other hand, perhaps you don’t think of yourself as one of the “weaker” ones in Jesus’ church. Perhaps you have been granted the gifts, social graces, and spiritual empowerment that have secured you a respected place among God’s children. Maybe you are typically the strong one in your relationships, usually helping others along, often leading. You feel weak the odd time, but generally people admire you, want to be around you, and want to be like you.

If so, that’s okay. It’s not wrong to be strong (how’s that for a slogan?), as long as you remember that your strength is actually God’s strength, and that it won’t always be yours. Just as “weaker” Christians are indispensable, so are “stronger” ones.

How, then, should a “stronger” Christian relate with “weaker” Christians? This question deserves books; I will discuss one sentence of Scripture. Consider this four-point sermon outline from Paul:

And we urge you, brothers, admonish the idle, encourage the fainthearted, help the weak, be patient with them all. (1 Thess. 5:14)

Paul is matching the cure to the disease. He identifies three types of Christians with problems: the idle, the fainthearted, and the weak. And he names three responses to these Christians: admonish, encourage, and help. The way he pairs these responses with these “problem Christians” is most instructive.

The “idle” are disorderly, disruptive, and unruly. They are not so much lazy as “busy doing the wrong things,”1 such as being busybodies and spreading false teachings. These people need to be “admonished”—firmly warned and even disciplined if necessary (cf. 2 Thess. 3:6, 14-15).

The “fainthearted” are timid and discouraged. They may be worried, sad, or low on faith. “These people did not need to be admonished but persuaded not to give up.”2 If “encouraged,” they will succeed.

The “weak” may be the least specific category. The word here is a variation of the same word translated “weaker” in our main passage, 1 Corinthians 12.3 Here, as there, commentators suggest diverse references, such as spiritual shortcomings, physical sickness, economic need, low social status, or psychological weakness. Whatever the case, what these people need is “help.”

Our English word “help” may be too vague and weak, however. The same Greek word4 is found three places in the New Testament, where it is translated as “be devoted to” (Matt. 6:24; Luke 16:13) or “hold firm to” (Tit. 1:9). The word seems to imply proximity, focus, and allegiance. Someone who “helps” in this sense will not hold others at a distance, will not devalue or forget them, and will not reject them. Paul is saying we should “take an interest in [the weak], pay attention to them, and remain loyal to them… Those whom society walks over and puts down are lifted up and given support by the church.”5

Finally—point four in Paul’s outline—all three kinds of Christians require, and must be offered, patience.

AT THE PIANO: WHEN ONLY HELP WILL HELP

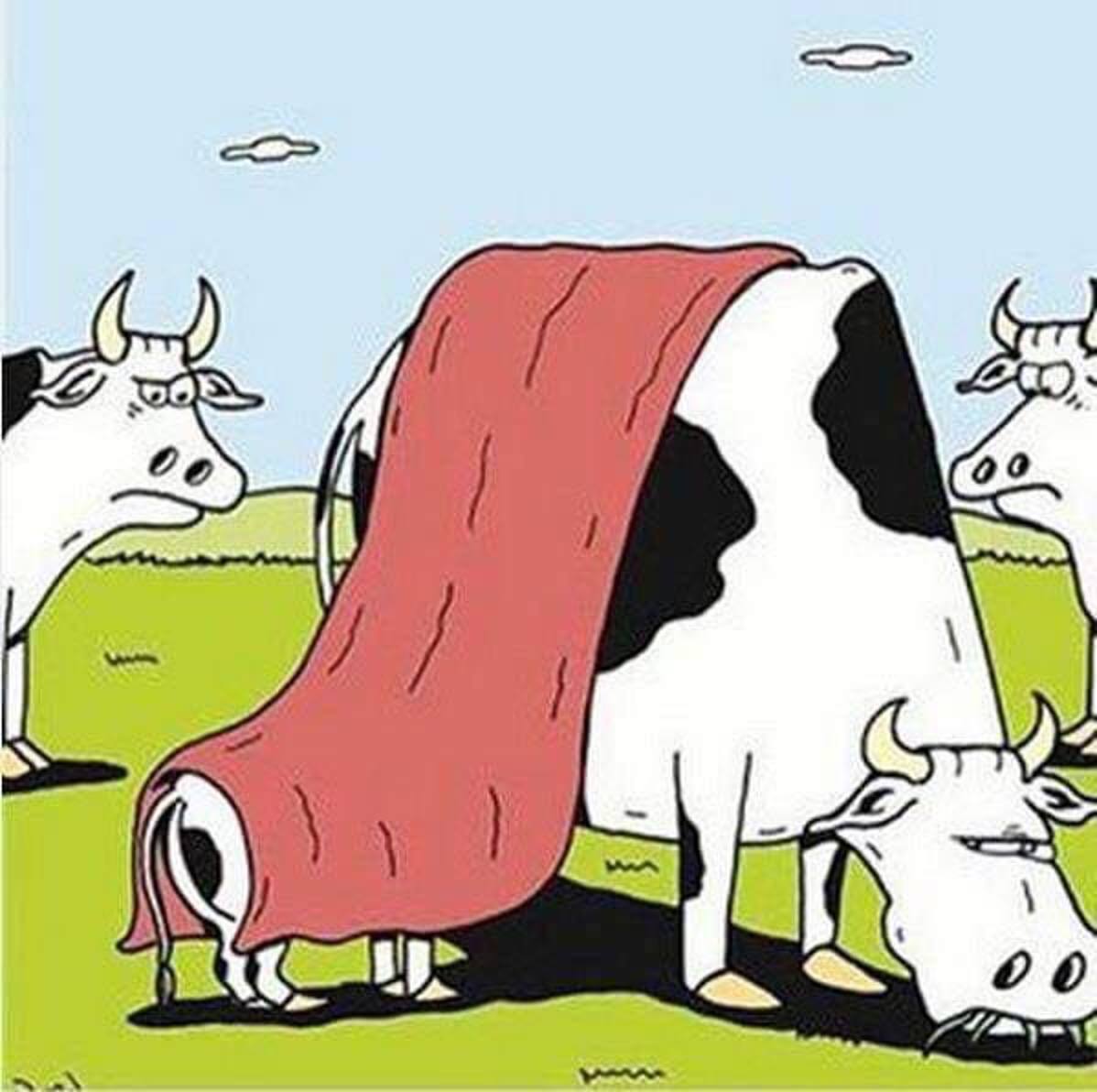

In identifying the “idle,” “fainthearted,” and “weak,” Paul seems to be describing three levels of ability: Those who are able and active but unruly, those who are able but inactive because discouraged, and those who are unable and need help. Because of these differing levels of ability, offering the correct response is crucial.

What will happen if we give the unruly encouragement or help? They will probably abuse them. What will happen if we warn the fainthearted? Their discouragement will only deepen. And if we help them without encouraging them? They may never learn to do what they, with encouragement, could do for themselves.

And what about the weak? What if we warn them? What if we feed them motivational words? What will warnings and “encouragements” do to their souls if they are truly unable, for whatever reason, to do what we are expecting them to do?

Let me illustrate. Recently we hosted a piano recital in our home. Each of my three daughters played a solo. One of my daughters is developing socially somewhat more slowly than her sisters. She turns inward when she is asked to interact with new people.

When this daughter’s turn came, I asked her aloud, “Do you want to tell us what song you’re playing?” Immediately I read on her silent face the expected answer: No. So I whispered to her, “Shall I say it?” Yes, she nodded. She then relaxed, I introduced her song, and we were treated to a lovely, sensitive performance of “Silent Night.”

You can catch the tail end of our daddy-daughter conversation here, along with her performance:

Now what would have happened if, when my daughter communicated that she did not want to introduce her song, I had admonished her in front of a living room full of people? “Why are you being stubborn? Don’t you realize that you are dishonoring our guests? We can wait here until you find enough respect to talk.” As her dad, I simply can’t imagine saying anything like this.

What if, instead of rebuking her, I had encouraged her, saying “You can do it!” or “Don’t be afraid!” or “Everyone here is friendly, you’re safe.” While this would have been less damaging, it still wouldn’t have been pretty. Suddenly the girl who was already trying to avoid attention would have been thrust doubly into the center of everyone’s focus. Shame and fear would have washed over her. Even if she had eventually found words, her piano performance would probably have suffered.

No, what my daughter needed in that moment was not admonishment, not encouragement, but help. We’ve all been there! She needed someone who was devoted to her and who would care for her. She needed me to speak for her. And when I gave her the help she needed, she freely shared her gift with the group—a pleasing performance of a carol she had diligently prepared. As her father, I was, and am, delighted and proud.

“Strong” Christians, what was true for my daughter is equally true for the “weaker” Christians in our midst. While every Christian benefits from regular encouragement, and we all need warning from time to time, what “weak” Christians need most of all is help.

What that special needs teen needs is someone to continually give him attention by rubbing his back, so he doesn’t feel a need to speak out during the service—and a congregation who will laugh good-naturedly when he does. What that post-operation preacher needs is someone to read his sermon for him. What that immigrant family needs is an opportunity to share a song in their own language. What that timid music team member needs is permission to look down at her music instead of at the congregation, so she is not distracted from worship by social anxiety.

I witnessed each of these and more yesterday at the church we visited.

Sure, it takes a lot of patience sometimes, but what “weak” Christians need most of all is help.

PHYSICIANS OF THE SOUL

Christians, then, must learn to be what the Puritans called “physicians of the soul.” We must learn to not only note symptoms but also diagnose diseases correctly and then apply the right cures.

The easiest thing for all of us, of course, is to note symptoms—some dishonorable behavior in our “weaker” brother or sister—and then diagnose them based on our knowledge of ourselves. “If I acted the way he did, I would be stubborn, selfish, or unrepentant.” But I am not him and you are not me, and essentially identical symptoms may be caused by very different diseases. We need to listen devotedly to our “weaker” brother or sister, learning to know them well. If not, we will diagnose wrongly and could apply a “cure” that actually worsens their disease.

Tim Keller has written a helpful article about the Puritans and soul care. Here are a few excerpts:

The Puritans had sophisticated diagnostic casebooks containing scores and even hundreds of different personal problems and spiritual conditions. John Owen was representative when he taught that every pastor must understand all the various cases of depression, fear, discouragement, and conflict that are found in the souls of men. This is necessary to apply “fit medicines and remedies unto every sore distemper.” Puritans were true physicians of the soul. Their study of the Scripture and the heart led them to make fine distinctions between conditions and to classify many types and sub-types of problems that required different treatments…

In addition, the Puritans were able to make fine distinctions in diagnosing the root causes of the problems. [Richard] Baxter’s sermon, “What are the Best Preservatives against Melancholy and Overmuch Sorrow?” discerns four causes of depression (sin, physiology, temperment, and demonic activity) which can exist in a variety of interrelationships…

The Puritans’ balanced understanding of the roots of personal problems is not mirrored in the pastoral practice of modem evangelicals. Most counselors tend to ‘major’ in one of the factors mentioned by Baxter. Some will see personal sin as the cause of nearly all problems. Others have built a counseling methodology mainly upon an analysis of “transformed temperments.” Still others have developed “deliverance” ministries which see personal problems largely in terms of demonic activity. And of course, some evangelicals have adopted the whole ‘medical model’ of mental illness, removing all ‘moral blame’ from the patient, who needs not repentance but the treatment of a physician.

But Baxter not only shows an objective openness to discovering any of these factors in diagnosis, he also expects usually to find all of them present. Any of the factors may be the main factor which must be dealt with first in order to deal with the others.

So we see sophistication of the Puritans as physicians of the soul… Biblical counselors today, who sometimes are rightfully charged with being simplistic, could learn from the careful diagnostic method of these fathers in the faith…

Most of us talk less about sin than did our forefathers. But, on the other hand, the Puritans amazingly were… extremely careful not to call a problem ‘sin’ unless it was analyzed carefully. One of their favorite texts was: “A bruised reed he will not break, and a smoking flax he will not quench” (Matthew 12:20). 6

This, then, is my advice to “strong” Christians: seek to be physicians of the soul. We won’t always get it right, of course. But do not assume everyone is as strong as you are. If someone’s symptoms are due primarily to weakness, then be very slow to offer warning. Be judicious even in how you offer encouragement. Aim primarily to offer help.

Understand, however, that help is not help, biblically speaking, unless it is an expression of authentic devotion and loyalty. In fact, be wary of communicating that you are providing help. Seek ways to personally share in the suffering of the “weaker” members of Christ’s body, experiencing empathy and not merely offering sympathy.

Join God in honoring your “weaker” brothers and sisters, that your mutual joy may be full. Remember that God is the one who placed both of you in his composition. All colors are indispensable there, not just your brilliant ones. Mourn when your strength inhibits Christ’s grace. Offer help to the “weak” with great patience and devotion. Don’t, by holding them at a distance, miss an opportunity for God to increase the unity of Christ’s church.

This post grew beyond my expectations. I want to speak a final word primarily to “weaker” Christians in my final post. (And don’t we all have at least one turn being weak?)

But for now, I invite your responses to this post. I’m sure I’m missing a lot that should be said, so likely my balance isn’t perfect. Did you find something here helpful? Do you have more to add? Please share your insights in the comments below. And thanks for reading.

- G.K. Beale, 1-2 Thessalonians, IVP New Testament Commentary Series (Downers Grove, IL: IVP Academic, 2003), 164. ↩

- Gene L. Green, The Letters to the Thessalonians, Pillar New Testament Commentary (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2002), 253. ↩

- The lexical form for the words in both texts is ἀσθενής. ↩

- Lexical form: ἀντέχομαι. ↩

- Green, ibid., 254. ↩

- Tim Keller, “Puritan Resources for Biblical Counselling,” blog post, June 1, 2010, Christian Counseling and Educational Foundation, https://www.ccef.org/resources/blog/puritan-resources-biblical-counseling, accessed December 5, 2018. ↩