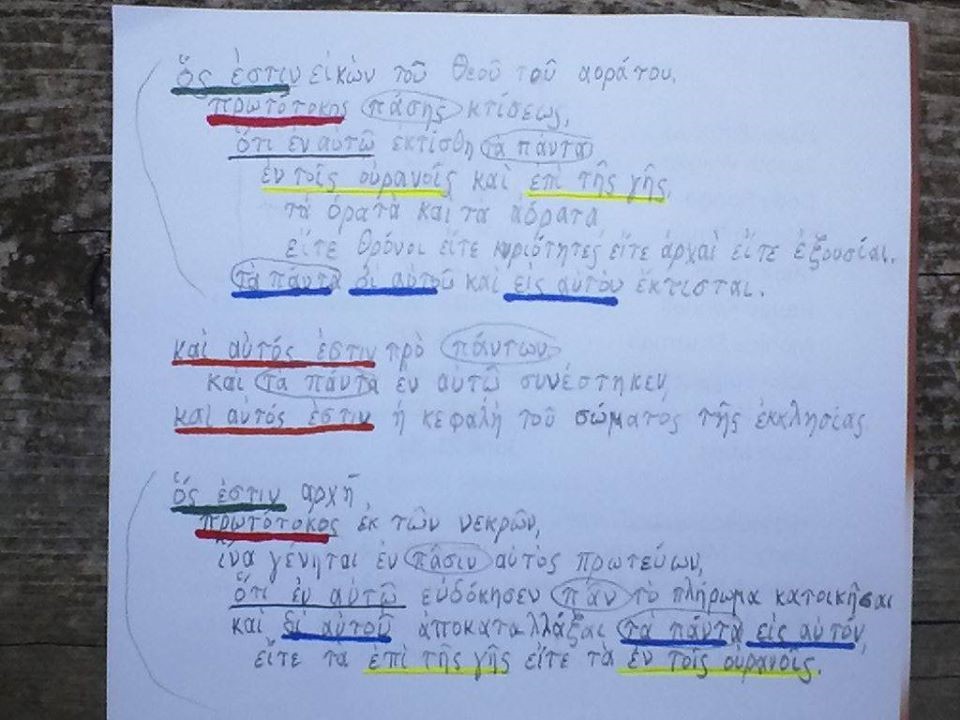

Our church is enjoying a sermon series through Paul’s letter to the Colossians. At the start of the series, it was suggested that the musicians in our midst might want to compose new songs based on the letter. I immediately thought of the “hymn” in Colossians 1:15-20 and decided I’d like to put it to music. This task has proven difficult however, since the passage doesn’t follow the rhythms or rhymes of English poetry, despite being full of other poetic features.

This week I meditated on the passage again (in Greek and English) until I could more or less say it by memory (in English). On Wednesday some musical lines finally started to come, but I wasn’t very impressed. Thursday morning my wife recalled and played Andrew Peterson’s fine arrangement of this passage (“All Things Together“). Hearing Peterson further opened my musical streams and also gave me the idea of beginning each verse with questions. Finally better music started to come, and that day I composed most of this song.

After a couple more days of adaptations and valuable feedback from my family, I am content with the result. Today–the Saturday between Good Friday and Resurrection–my family and I recorded the song. Special thanks to my daughters for sharing their pleasant voices, which made the song so much better, and to my wife for willingly overseeing lights and camera.

I do not pretend this is great music, but I am happy that it meets my original goals of sticking closely to the biblical text and yet being singable by a congregation. I envision a soloist singing the questions at the start of each verse, with the congregation responding. The rest of each verse could be either sung by the soloist or, with a little practice, by the entire congregation. The chorus and bridge are simple for all to sing.

In writing this song I tried to follow the text of Colossians as closely as possible (using the ESV translation), with minor adjustments to ease the rhythm and retain clarity. I also tried to follow the original structure of this “hymn,” which has two stanzas (1:15-16 and 1:18b-20–the two verses of my song) tied together by several transitional lines (1:17-18a–the chorus of my song). There is an “extra” line in the second stanza of the song that breaks the rhythm–an exclamation that Jesus is preeminent (first) not only in the original creation, but also in the new creation. I saved that line for the bridge of my song.

Bible students may recall that this passage is sometimes called a “Christ hymn”; it is often praised for its “high Christology.” While it is true that this passage describes Jesus in terms fitting for an anointed king, the word “Christ” itself is conspicuously missing from the passage and its immediate context. Instead, we find the language of sonship: “the Father… delivered us from the domain of darkness and transferred us to the kingdom of his beloved Son” (Col. 1:12-13). This sonship language ties directly into the firstborn imagery in the hymn.

These observations explain the answers I provided to the opening questions in each verse. Who is the One whom the song discusses? “Jesus, God’s own Son”; “Jesus, the Son of God.”

Here are the lyrics to the song:

BEFORE ALL THINGS

(Colossians 1:15-20)

Verse 1:

Who is the image of the invisible God?

Jesus, God’s own Son

Who is the firstborn of all creation?

Jesus, God’s own Son

For by him all things were created,

In heaven and on earth,

Visible and invisible.

Whether thrones, dominions, rulers

Or authorities

All were created through him and for him.

Chorus A:

And he is before all things

He is before all things

And all things in him hold together

He is before all things

He is before all things

And he is the head of the body, the church.

Verse 2:

Who is the beginning?

Jesus, the Son of God

Who is the firstborn from the dead?

Jesus, the Son of God

For in him all the fullness

Of God was pleased to dwell

And reconcile through him all to him

By the blood of his cross

Making peace with all

All whether on earth or in heaven.

(Chorus A)

Bridge:

He’s the firstborn of all creation

The firstborn of all creation

That in all things he might be first

And the firstborn from the dead

The firstborn from the dead

That in all things he might be first

You’re the firstborn of all creation

The firstborn of all creation

That in all things you might be first

And you’re the firstborn from the dead

The firstborn from the dead

That in all things you might be first

Chorus B: (2x)

And you are before all things

You are before all things

And all things in you hold together

You are before all things

You are before all things

And you are the head of the body, the church.

You are the head of the body—You’re first!

Optional ending: (Repeat as desired)

Jesus, you are first

In all things you are first

In all things you hold first place of all

Jesus, you are first

We worship you as first

We worship you as first over all

Copyright April 9, 2020 by Dwight Gingrich. To be freely used for nonprofit uses only by the church of Jesus. All other rights reserved.

Is there a passage of Scripture that you have wished was set to music? Do you have any feedback on my efforts here? You may share your thoughts in the comments below.

If you want to support more writing like this, please leave a gift: